Mary Phagan-Kean and the Legacy of the Leo Frank Case: A Family’s Perspective on Historical Memory and Revisionism

by Ethan Murphy

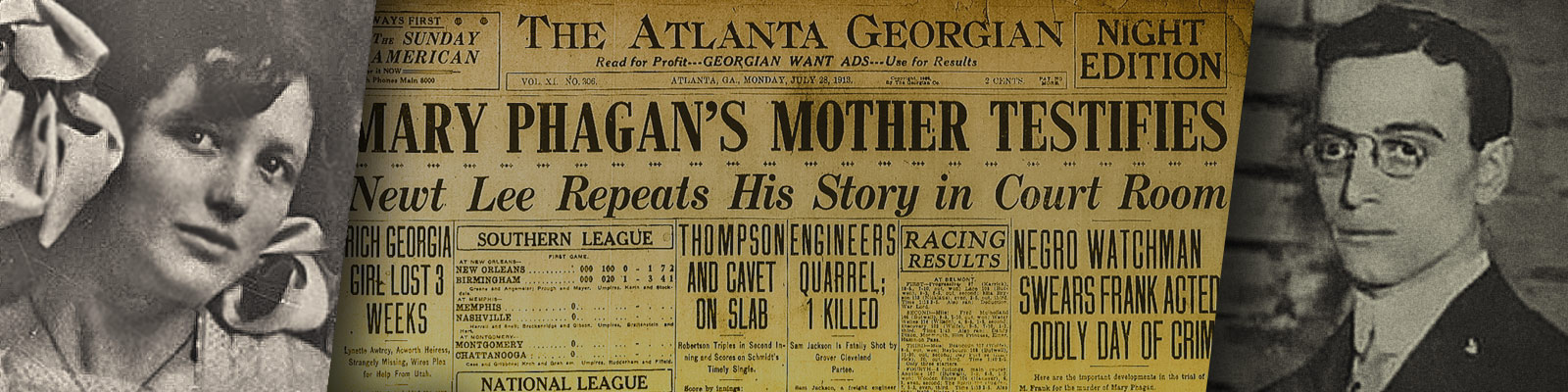

IN THE early 20th century, the murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old factory worker in Atlanta, Georgia, and the subsequent trial and lynching of her employer Leo Frank, catalyzed a national debate over justice, antisemitism, and media influence. More than a century later, the case remains one of the most analyzed and contested in American legal history. Among the voices often excluded from contemporary discourse is that of the Phagan family itself. Mary Phagan-Kean, a grandniece of the victim and her namesake, has spent the better part of six decades engaged in original research, archival preservation, and public advocacy concerning the legacy of her relative’s death.

Phagan-Kean was not raised with knowledge of her familial connection to the case. Born in 1953, she first learned about the 1913 murder at age thirteen from a teacher in South Carolina who asked whether she was related to “the little girl who was murdered in Atlanta.” The question marked the beginning of a lifelong inquiry. After confronting her father, she learned for the first time that her great-aunt’s murder had been the subject of a nationally publicized trial and subsequent lynching. Her father, William Joshua Phagan Jr., confirmed that the victim was their relative and that Leo Frank had been convicted of the crime—a conviction the family had never questioned.

That initial conversation led Phagan-Kean to the Georgia Archives, where she encountered one of the most iconic images associated with the case: a photograph of Leo Frank’s lynching by vigilantes in Marietta, Georgia. Phagan-Kean recalls the encounter with the archival image as a formative moment, deepening her resolve to investigate the case further. Over the years, she amassed thousands of pages of documentation—including court records, newspaper clippings, correspondence, and private testimony—eventually donating her collection to the Georgia State Library for public access.

Phagan-Kean’s views sharply diverge from modern campaigns to posthumously exonerate Frank. She holds to the original jury’s verdict and argues that the movement to absolve Frank—driven in large part by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), established in 1913 partly in response to the case—reflects not a reassessment of the evidence, but rather a political and ideological reinterpretation of historical facts.

In 1982, a pivotal moment occurred when Alonzo Mann, who had been a teenage office assistant at the National Pencil Factory in 1913, came forward with a new claim. Mann asserted that he had seen the factory’s African American janitor, Jim Conley, carrying Mary Phagan’s body on the day of the murder, implying that Conley—not Frank—was the true culprit. Mann’s statement, delivered nearly 70 years after the fact and publicized through a series of newspaper features, formed the basis for renewed appeals to the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles.

Phagan-Kean responded swiftly. She reached out to the Board, seeking participation in any hearings or deliberations. She was told that no public presentations were planned. In 1983, the Board declined to issue a pardon. However, in 1986, it reversed course, granting Frank a limited posthumous pardon—not on the grounds of innocence, but due to the state’s failure to prevent his extrajudicial death. The Board made clear that it was “making no statement as to guilt or innocence.” Phagan-Kean has described this as a deeply unsatisfactory resolution that bypassed her family and ignored substantial elements of the trial record.

In interviews, Phagan-Kean expresses particular concern over what she sees as an erasure of historical context and suppression of documentary evidence. For example, she highlights the disappearance of the full trial transcript during the research phase of Harry Golden’s A Little Girl is Dead (1965), which advanced the theory of Frank’s innocence. Although a brief of evidence remains, the full transcript has never resurfaced, raising questions about the integrity of later scholarship.

Phagan-Kean further notes that the case has frequently been presented through the lens of antisemitism—particularly in media portrayals such as the 1988 miniseries The Murder of Mary Phagan and in recent advocacy for a new pardon initiated in 2023. While acknowledging the existence of antisemitism in the early 20th century, Phagan-Kean challenges the claim that it was the determinative factor in Frank’s conviction. She points to testimony from factory workers, circumstantial evidence, and inconsistencies in Frank’s own statements as the foundation for the jury’s decision.

Her critique extends to what she describes as the media’s role in shaping collective memory. “Every few years, they resurrect Leo Frank as a martyr,” she states, arguing that these portrayals neglect the primary sources and trial record in favor of narrative cohesion. In her forthcoming revised edition of The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, she adds sixteen new chapters addressing recent developments and offers a direct rebuttal to those advocating for Frank’s full exoneration.

Although she has historically declined public appearances, Phagan-Kean has chosen to speak out in recent years due to what she views as increasing distortions of the historical record. She is careful to clarify that her advocacy is not rooted in animus, but in a sense of duty to her family and to the principle of historical integrity. “This is not about hate,” she says. “It’s about truth. The evidence is there. People just have to read it.”

Phagan-Kean’s position raises important questions about how historical memory is constructed, contested, and preserved. While scholarship on the Leo Frank case often focuses on legal procedures, racial and religious dynamics, and early 20th-century southern culture, the voice of the victim’s family adds a crucial, if frequently overlooked, dimension. Her insistence on fidelity to the trial record, skepticism toward retrospective testimony, and wariness of political motivations invites reconsideration of how history is written—and who gets to write it.

In a time when historical narratives are under increasing scrutiny and revision, Mary Phagan-Kean’s contribution serves as a reminder of the complex interplay between memory, justice, and identity. Whether or not one agrees with her conclusions, her exhaustive archival work and her steadfast commitment to public access make her an essential figure in the ongoing conversation surrounding one of America’s most polarizing criminal cases.