Conley Tells in Detail of Writing Notes on Saturday at Dictation of Mr. Frank

Atlanta Journal

Wednesday, May 28th, 1913

Negro Declares He Met Mr. Frank on the Street and Accompanied Him Back to the Factory, Where He Was Told to Wait and Watch—He Was Concealed in Wardrobe In Office When Voices Were Heard on Outside, It Is Claimed

NEGRO LOOKED UPON AS A TOOL NOT PRINCIPAL DECLARE DETECTIVES WHO HAVE QUESTIONED HIM

Chief Beavers Confer With Judge Roan In Reference to Taking Conley to Tower to Confront Frank but Is Told That It Is a Question for Sheriff to Decide—No Effort In This Direction Likely Until Mr. Rosser Returns to City

“Write ‘night-watchman,’” the city detectives are said to have commanded James Conley, negro sweeper at the pencil factory, in jail Wednesday.

The result is said to have been “night-wich.”

So also the note found beside the dead body of Mary Phagan spelled it.

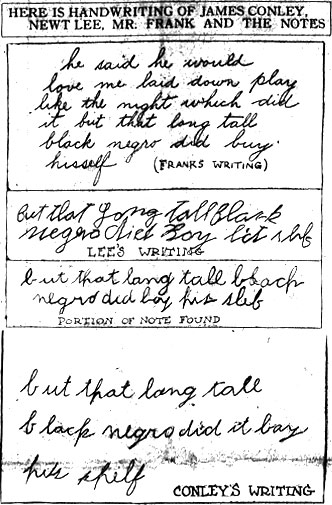

The detectives regard this strongly corroborative of Conley’s admission that he himself wrote the notes found beside the dead girl. Conley declares that he wrote them, however, at the dictation of Leo M. Frank, superintendent of the pencil factory, under indictment for the murder. The detectives are disposed to place full credence in his story now, it is said, since he has declared that he did the writing on Saturday afternoon instead of on Friday afternoon as he first swore, and has gone into details.

A new and lengthy affidavit, going into detail in sequence throughout the day of the fatal Saturday, was sworn to by the negro in the detective headquarters Wednesday morning.

In it the negro recited as minutely as he could remember them, his actions and movements upon the day.

Shortly after 10 o’clock he was standing at the corner of Forsyth and Nelson street, he now swears, when Leo M. Frank, superintendent at the factory, his employer, came past, going toward Montag Brothers. Mr. Frank told him to wait there until he came back, swears the negro. Some minutes afterward Mr. Frank returned and took him, the negro, to the factory. Mr. Frank sat him down on a box besides the stairs, said the negro, and told him (the negro) to wait there and “see what he could see.” He would call with a whistle, said Mr. Frank, when he wanted the negro.

“Be careful not to let Mr. Darley see you,” the negro swears Mr. Frank told him.

Conley continued in detail his affidavit, it is said, describing several people who entered and left and whose presence at the factory already has been established clearly. After about an hour, the negro swears he grew sleepy. He had had a beer, and he was in a comfortable position and everything was quiet; so he dozed off to sleep, he said, and didn’t remember anything more until he heard somebody [w]histle sharply close at hand and looked up and saw Mr. Frank standing in the doorway at the head of the stairs.

SAID MR. FRANK WAS SHAKING.

He aroused himself and responded to Mr. Frank’s call. At the head of the stairs Mr. Frank, caught him under the arm, swears the negro. Mr. Frank was shaking and trembling violently.

It gave him the impression, swears the negro, that Mr. Frank wanted to keep him from looking towards the back.

Mr. Frank led him, the negro, thus into his (Mr. Frank’s) office.

As they passed the time clock, the negro sears, he happened to notice that it was 4 minutes to 1 o’clock.

According to Mr. Frank’s sworn testimony to the coroner’s jury before he himself was accused formally, Mary Phagan, the murdered girl, had received her pay and gone before that hour.

They went clear back into the inner office, swear[s], the negro, Mr. Frank saying nothing, but holding tightly to his arm. Hardly had they entered there and gotten ready to sit down when people were heard approaching in the outer part of the factory. Mr. Frank put him into a big wardrobe in the office, swears the negro and shut the doors of it and then went out and met the visitors or received them in the inner office, but dismissed them soon and let the negro out when all was quiet again.

DICTATED WHAT NEGRO WROTE.

Then, swears the negro, Mr. Frank told him he wanted to get a sample of his handwriting. He dectated [sic] what the negro wrote. Mr. Frank was trembling, swears the negro. His hands shook, and he ran his fingers through his hair. He said in an undertone as he walked up and down, swears the negro, addressing not him but seemingly talking to himself: “There’s no reason why I should hang.” The negro said when he had finished writing what Mr. Frank dictated, Mr. Frank thanked him warmly, and said he wouldn’t forget him (the negro), and called him a good negro, good boy, etc. and gave him $2.50, and even led him to the door at the head of the stairs. After that, the negro swears, he didn’t see Mr. Frank until Tuesday morning.

The negro swears that he remembers that one of the notes began “Dear Mother.”

The negro reiterates steadfastly, it is said, that he did not see Mary Phagan at all on the day of the murder.

He left the factory about ten minutes after 1 o’clock swears the negro.

CONFERS WITH JUDGE ROAN.

Chief Beavers has not made application to Judge L. S. Roan for a formal order on the sheriff to permit him to take Conley to the jail for the purpose of confronting Frank with the negro.

The chief did confer with Judge Roan Wednesday afternoon and was advised by the latter that the matter was one for the sheriff to decide. Judge Roan, it is understood, informed the chief that under the law Frank would be entitled to consult his attorney and have him present should a meeting between the negro and Frank be arranged.

Attorney Rosser, Frank’s counsel, is at present at Clayton, Rabun county, engaged in the trial of the Tallulah Falls suit.

It is not known whether the chief will make any further efforts to get the negro face to face with Frank.

The fear that he would hang if he had admitted writing the notes after Mary Phagan went to the factory, is given by the negro as his reason for first saying that he wrote the notes on the day before the crime.

Conley still claims that he had no knowledge that a crime had been committed in the building. The detectives do not regard Conley in the light of an accomplice, but simply as an unwitting tool.

Just after his arrest it is said that Conley told many different stories to the police and they caught him in a number of lies.

For the first two weeks of his incarceration, it is said, he maintained that he could not write.

The detectives, however, found where he had bought two watches on the installment plan, and had filled out “deeds” for them.

They compared this writing, they say, with the writing on the notes found by the slain girl’s body and found it identical. Then they secured other specimens of his handwriting, and confronted him with them. It was a short time after this that he called for Detective John Black and admitted writing the two notes.

Then Chief of Detectives N. A. Lanford, Chief J. L. Beavers, and Harry Scott, of the Pinkertons, took the negro from police headquarters to the Tower in order that he might make his statements before Superintendent Frank.

Sheriff Wheeler Mangum sent word to Frank, and he stated that he did not wish to see the officers or Conley unless his attorney, Luther Z. Rosser, was present. Without Frank’s agreement the sheriff would not allow the officials to visit the accused man’s cell, and the attempt was given up.

DO NOT SUSPECT CONLEY.

Contrary to published reports, the detectives and others interested in the investigation of the Phagan murder have never for a moment entertained the suggestion that James Conley, the negro sweeper, was guilty of the crime or that he had any further hand in it than to write the notes, which he says he wrote at the dictation of Frank.

The officers regard Conley as their most material witness. They declare that he connects up all the circumstantial evidence gathered by them. They do not believe that he had any hand in the actual murder or that he knew one had been committed until after the girl’s body was found.

GENTRY IN HIDING.

George W. Gentry, the young stenographer who took the dictograph conversations in the Williams house last week, has been reported to the police as missing.

According to members of his family, the young man left his house to avoid the many people who came to question him about the dictograph conversations, and members of his family do not fear for his safety and are now in communication with him.

Young Gentry left home early Monday morning and neither his mother nor other members of his family at 32 East Alexander street have seen him since that time.

He left following an interview with a man, who posed as a newspaper reporter, and who told young Gentry that he was in danger of being arrested on a trumped up charge.

Members of his family do not think, however, that his threat was as much responsible for his risapperance [sic] as the general annoyance of repeated questions about the famous dictograph records.

Young Gentry has telephoned his home each day since he left and his mother heard from him Wednesday afternoon.

Members of the family expect the young man to return when the excitement over the publication of the dictograph records has subsided.

The detectives working on the case manifestly were pleased with the negro’s new statements. They declare their firm belief that he is telling the truth, and point to the corroborative effect of numerous details already established—regarding, for instance, those who entered and left the factory, etc.

Harry Scott, of the Pinkerton agency, was quoted Wednesday afternoon as expressing confidence that Frank will be convicted.

Alabama Police Have New Phagan Suspect

A. E. Williams, chief of police of Alabama City, Wednesday telephoned to Chief of Police James L. Beavers that there was a man named Bryant in that town who was acting in a very suspicious manner and it was intimated that he might know a great deal about the Phagan case.

This message was referred to Detective Chief Lanford, who said that he had never heard of anyone named Bhyant [sic] in connection with the Phagan case, but that he would look into the matter. He does not, however, lay any stress on the message from Alabama City.

Lanford and Felder Exchange New Thrust

Satire has been emphasized in the controversy between Colonel Thomas B. Felder and the police department by the issuance by Chief of Detectives N. A. Lanford of the following statement:

“I will make this proposition to Colonel Felder: That I will handcuff A. S. Colyar and send him back to Knoxville, Tenn., without requisition papers, if he (Colonel Felder) will accompany one of my men to Columbia, S. C., waiving requisition papers. Thereby I would get rid of two nuisances.

(Signed) “N. A. LANFORD.”

To the detective’s proposition, Colonel Felder has made this reply:

“There is only one difference between those crooks, Lanford and Colyar—one has been caught and the other has not.”