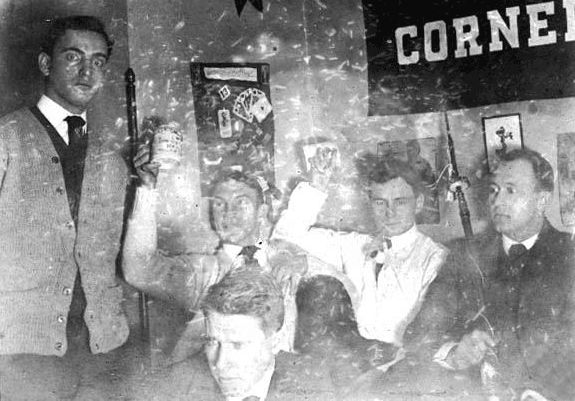

The trial of Leo Frank (pictured) for the murder of Mary Phagan ended its third week 100 years ago today. Join us as we break through the myths surrounding the case and investigate what really happened.

by Bradford L. Huie

AS THE THIRD WEEK of the trial dawned, the prosecution had just made its case that National Pencil Company Superintendent Leo Max Frank had murdered 13-year-old laborer Mary Phagan — and a powerful case it was. Now it was the defense’s turn — and the defense team was a formidable one, the best that money could buy in 1913 Atlanta, led by Reuben Arnold and Luther Rosser. And many would argue that the city’s well-known promoter and attorney Thomas B. Felder was also secretly working for Frank and his friends, along with the two biggest detective agencies in the United States, the Burns agency — sub rosa, under the direction of Felder — and the Pinkertons — openly, cooperating with the police, and under the direction of the National Pencil Company. (For background on this case, read our introductory article, our coverage of Week One and Week Two of the trial, and my exclusive summary of the evidence against Frank.)

As the defense began its parade of witnesses, few suspected that the defendant himself, Leo Frank, would soon take the stand and make an admission so astonishing that it strained belief.

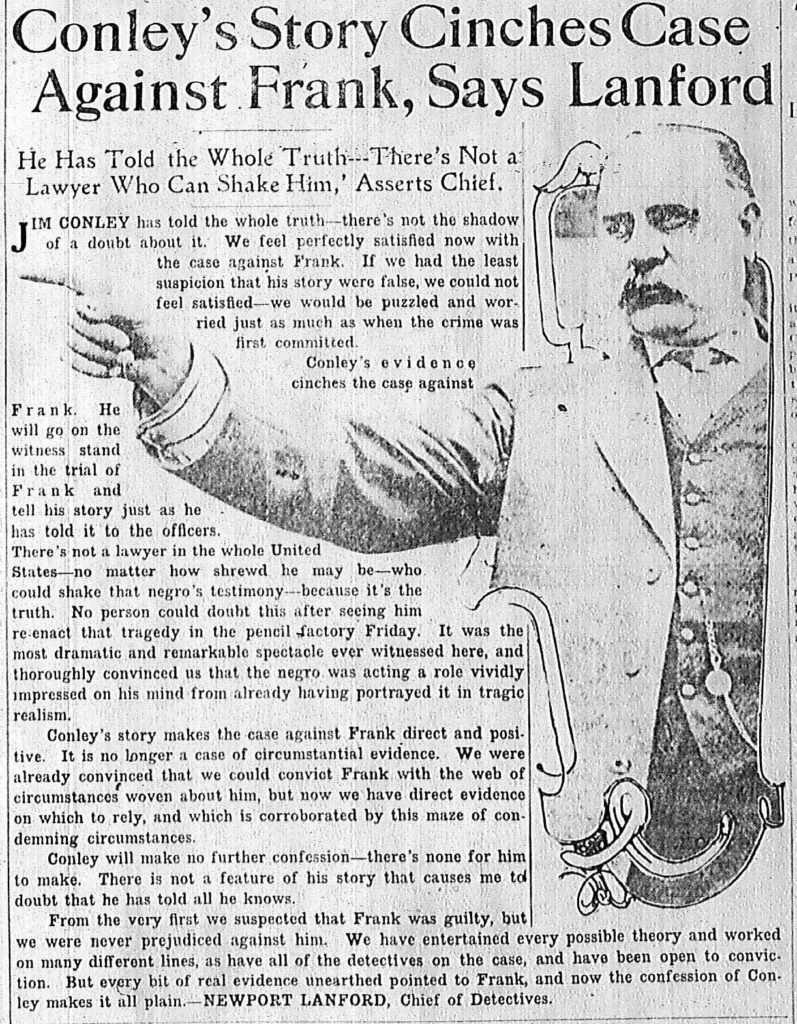

The testimony of Jim Conley for the prosecution was still fresh in every spectator’s and juror’s mind. Conley, an African-American sweeper for the pencil company, had admitted to helping Leo Frank move the lifeless body of Mary Phagan from the pencil factory’s Metal Room bathroom on the second floor to a spot in the basement just in front of the gaping maw of the furnace, adding that Frank had asked him to come back later and burn the body in return for a promised payment of $200 — an appointment that was never kept. He also told a rapt courtroom how he had written the black-dialect “death notes” at Frank’s instruction.

Conley said that Frank had admitted to striking the girl, when she refused his advances, and accidentally killing her. (Conley evidently missed seeing the marks of strangulation, probably being deceived by a ripped piece of lace underwear that the killer had placed around Mary’s neck to conceal the deep lacerations made by the cord.)

Not only had Conley stood up to one of the most intense cross-examinations imaginable, but, before the trial, he had led investigators on an on-location step-by-step re-enactment of his part in the crime that was so detailed and factual that it convinced almost all observers that he was telling the truth. The Atlanta Georgian‘s James B. Nevin, whose paper was beginning to show sympathy for Frank, nevertheless expressed the popular view when he wrote:

If the story Conley tells IS a lie, then it is the most inhumanly devilish, the most cunningly clever, and the most amazingly sustained lie ever told in Georgia!

W.W. Matthews, a motorman for the Georgia Railway & Electric Co., was sworn for the defense and stated that Mary Phagan got off his car at 12:10, meaning that if the motorman’s watch and memory were accurate she must have arrived shortly after Monteen Stover, not before her as other witnesses had testified. W.T. Hollis, a streetcar conductor, was called to confirm Matthews’ timing. Here is their testimony:

W.W. MATTHEWS, sworn for the Defendant.

I work for the Georgia Railway & Electric Co. as a motorman. On the 26th day of April I was running on English Avenue. Mary Phagan got on my car at Lindsey Street at 11:50. Our route was from Bellwood to English Avenue, down English Avenue to Kennedy, down Kennedy to Gray, Gray to Jones Avenue, Jones Avenue to Marietta, Marietta to Broad, and out Broad Street. From Lindsey Street to Broad Street is about a mile and a half or two miles. We make frequent stops. We were scheduled to arrive at Marietta and Broad at 12:07(1/2). We were on schedule. We stayed on time all day. Our car turned up Broad St.

Mary Phagan got off at Hunter and Broad. It takes generally from two and a half to three minutes to go from Broad and Marietta to Broad and Hunter. That is a very congested street and you must go slow. I was relieved at Broad and Marietta by another motorman, but sat down in the same car one seat behind Mary Phagan. Another little girl was sitting in the seat with her. We got to Broad and Hunter about 12:10. Mary and the other little girl both got off and walked to the sidewalk and they wheeled like they were going to turn around on Hunter Street, both of them together. The pencil factory is about a block and a half from where they got off at Hunter and Broad. Nobody got on with Mary at Lindsey Street. There wasn’t any little boy with her. The first time I noticed the little girl sitting with Mary was when we left Broad and Marietta Streets and I went back into the car and saw this little girl sitting with her. I know the little Epps boy. I have seen him riding on my car. He did not get on the car with her at Lindsey Street. I saw Mary’s body at the undertaker’s. It was the same girl that got on my car.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I did not tell one of the detectives that we might have been running three or four minutes ahead of schedule that day. I remember that Mary did not get off the car at Broad and Marietta because there was a street car conductor sitting behind me, an ex-conductor and he had a badge on his coat and I looked at it and it had a little girl’s picture and I reached over to where Mary was and said, “Little girl, here is your picture,” and she said, “No, it is not.” I don’t know who the other little girl was sitting with her. The other little girl was dressed something like Mary. I didn’t pay much attention to their dresses, but they looked sort of alike. Mary’s dress wasn’t black. It was light colored. I know Epps since this case came up. I could identify him. I never paid much attention to her hat. It was light colored I reckon but I am not sure. It just seemed that way.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

I identified Mary’s body Sunday afternoon after the murder at the undertaker’s. There was no doubt about her being the same girl. I knew her well by sight. She rode on my car lots.

RE-CROSS EXAMINATION.

I can’t tell you whether that is the hat or not she wore.

W. T. HOLLIS, sworn for the Defendant.

I am a street car conductor. On the 26th of April I was on the English Avenue line. We ran on schedule that day. Mary Phagan got on at Lindsey Street at about 11:50. She is the same girl I identified at the undertaker’s. She had been on my car frequently and I knew her well. No one else got on with her at Lindsey Street. Epps did not get on with her. I took up her fare on English Avenue, several blocks from where she got on. And no one was sitting with her then. I do not recollect Epps getting on the car at all that morning. Don’t know whether anybody else afterwards sat with Mary or not. We got to Broad and Marietta seven and a half minutes after twelve, schedule time. I was relieved at Forsyth and Marietta Streets, where I got off. Mary was still on the car when I got off. It takes two and a half minutes to run from Broad and Marietta to Broad and Hunter. I have timed the car again and again since then. I identified the little girl at the undertaker’s Sunday afternoon. Didn’t notice the color of her clothes.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

Mary rode with us two or three times a week. So did Epps. I don’t know where he got off or where he got on. We are not supposed to come in ahead of time. We never come in two or three minutes ahead of time. We are a little late sometimes. I never noticed anybody sitting with Mary. She was sitting by herself when I got her fare. There wasn’t but two or three passengers on the car and I know there wasn’t anybody sitting with her. If Epps was on the car I don’t recollect it. I don’t re- call the name of any other passengers except Mary Phagan. As to what attracted my attention to Mary getting on the front end of the car, as a general rule when she would catch our car Mr. Matthews would say to her “You are late to-day,” and sometimes she would come in and remark that she was mad; that she was late to-day and when she came that morning Mr. Matthews said to her, “Are you mad to-day?” and she said, “Yes, I am late.” And sort of laughed and came on in the car and sat down. She usually caught our car when she came in the morning, the one due in town at 7:07. I didn’t know Mary’s name, I just recognized Mary’s face as the little girl who traveled with us.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

I heard of the murder the next day. Newspaper reporters asked us to go down and identify the girl. There was no doubt about her being the little girl who was on our car. Oliver Street is the next street to Lindsey. I did not see Epps get on at Oliver Street. It is against the rule of the company to get to the city ahead of time.

RE-GROSS EXAMINATION.

It is not against the rules to get in behind time. Sometimes we might get there a few minutes ahead of time, but hardly ever. We always look at our watches at the main destination, just at Broad and Marietta. We are supposed to do that.

But — and this issue dogs both sides of this case — how accurate were watches and clocks in 1913? (Even in 2013, my quartz watch is sometimes off by a few minutes, especially when the battery is over a year old, and my remaining spring-wound watch is, to put it charitably, just approximate even when freshly-wound.) And, if Mary really didn’t get off the car until 12:10, why didn’t Monteen Stover meet her, then? And a later-arriving Mary Phagan still doesn’t explain Leo Frank’s empty office while the factory clock ticked off every second from 12:05 to 12:10 in Monteen Stover’s presence.

Herbert G. Schiff, the factory’s assistant superintendent directly under Leo Frank, then testified, stating that he’d never seen women brought to the office as the prosecution had alleged, nor had he seen Conley “watching” for Frank. He stated that he, not Frank, had paid off Helen Ferguson the Friday before the murder, and that Ferguson has not asked for Mary Phagan’s pay. He also went into excruciating detail — thousands of words’ worth — about how the books were kept at the factory, with the unstated implication being that Frank would have simply been too busy calculating sums and making entries to have entertained young ladies — or killed them. This “too busy” line of reasoning would be returned to again and again by the defense, and would form the larger part of Leo Frank’s own statement in his own defense. It was reinforced by the next witness, public accountant Joel Hunter, and yet another accountant, C.E. Pollard.

Hattie Hall, the plant stenographer, confirmed that she had worked with Frank until about noon, and had punched out at 12:02, seeing no one come in as she went out. Interestingly, Hall said of the important financial sheet that supposedly took up so much time every Saturday that “I didn’t see Mr. Frank working on any of these books that day, that I was in the outer office and he was in the inner office. There wasn’t any such looking sheet as the financial on his desk. When I was in there he was at work on a pile of letters and things like that.”

Hattie Hall, the plant stenographer, confirmed that she had worked with Frank until about noon, and had punched out at 12:02, seeing no one come in as she went out. Interestingly, Hall said of the important financial sheet that supposedly took up so much time every Saturday that “I didn’t see Mr. Frank working on any of these books that day, that I was in the outer office and he was in the inner office. There wasn’t any such looking sheet as the financial on his desk. When I was in there he was at work on a pile of letters and things like that.”

Emma Clarke Freeman and Corinthia Hall then testified that they had come briefly to the factory at 11:45, contradicting Jim Conley’s testimony that they had arrived at 12:45 when he had gone into Leo Frank’s wardrobe to hide from them while they talked to Frank. If the women spoke the truth, and it’s hard to imagine a reason for them not to do so, it does appear that Conley was mistaken about the time, but why would he deliberately lie about it? The timing of their visit isn’t crucial in any way — even its complete absence would just have given Frank and Conley a few more minutes to move Mary Phagan’s body and write the death notes. But it is interesting that, according to Conley’s testimony, Frank obviously didn’t want to be seen with Conley that day, which is odd and suspicious in itself — what’s wrong with being seen talking with the factory sweeper? Maybe a lot is wrong with it, if you’re planning to use him to facilitate a secret sexual tryst with an underage girl.

Pinkerton detective Harry Scott was recalled by the defense, mainly to show that Jim Conley had changed his story and contradicted himself thereby many times. But there wasn’t too much sting in that for the prosecution, since Conley himself had freely admitted as much.

Miss Magnolia Kennedy challenged the idea that Helen Ferguson had asked for Mary’s pay, but confirmed that the hair found on the lathe in the Metal Room looked like Mary’s, and that she had never seen blood on the floor there until after the murder:

MISS MAGNOLIA KENNEDY, sworn for the Defendant.

I have been working for the pencil factory for about four years, in the metal department. I drew my pay on Friday, April 25th, from Mr. Schiff at the pay window. Helen Ferguson was there when I went up there. I was behind her and had my hand on her shoulder. Mr. Frank was not there, Mr. Schiff gave Helen Ferguson her pay envelope. Helen Ferguson did not ask Mr. Schiff for Mary Phagan’s money. I came out right behind Helen Ferguson. We waited for Grace Hicks and then went down stairs. Helen didn’t say anything about Mr. Frank at all. We went down stairs about five minutes to six. We saw Helen Ferguson start up Forsyth Street.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

On Monday, April 28th, Mr. Barrett called my attention to the hair which he found on the machine. It looked like Mary’s hair. My machine was right next to Mary’s. There is a good deal of water over there by Mr. Quinn’s room. Mary’s hair was a light brown, kind of sandy color. You could plainly see the dark spots and white spot over it ten or twelve feet away. [The smear of Haskoline or other white substance, apparently placed over the blood spots. — Ed.] Helen and Mary were the best of friends and were neighbors. Helen made mention that Mary was not there when we were paid off. I have never noticed any spots around the metal room. That’s the first time I had ever seen anything like that.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

I have never looked for spots before. It’s a dirty floor, full of oil dirt. I don’t know whose hair that was. Helen did not ask Mr. Schiff for Mary’s money. She did not have any business going to Mr. Frank when Mr. Schiff was there paying off. She did not go in and ask Mr. Frank for Mary’s money. I left with her. I went one way and she went another.

RE-CROSS EXAMINATION.

Mr. Frank paid off sometimes. If there is any trouble about the amount of our money, we would go to anybody that was in the office. Mr. Frank was not paying off that day.

Pencil factory employee Wade Campbell was then sworn and told of his interactions on the day of the murder. The defense hoped he could cast doubt on the blood spot evidence and Frank’s interactions with Conley, but note well his testimony about how cheerful and playful Frank was before noon:

WADE CAMPBELL, sworn for the Defendant.

I have been working for the pencil factory for about a year and a half. I had a conversation with my sister, Mrs. Arthur White, on Monday, April 28th. She told me that she had seen a negro sitting at the elevator shaft when she went in the factory at twelve o’clock on Saturday and that she came out at 12:30, she heard low voices, but couldn’t see anybody. On April 26th, I got to the factory about 9:30. Mr. Frank was in his outer office. He was laughing and joking with people there, and joked with me. He thought I wanted to borrow some money. I stayed about five or ten minutes and left the factory. That was about 9:40. I have never seen Mr. Frank talk to Mary Phagan. On Tuesday after the murder I went up on the fourth floor with Mr. Frank. I did not see the negro Conley talk to him at all that time.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

My sister said she saw the negro when she went in the factory. When she heard the voices coming out, she was coming down the steps from the second floor. I saw the spots where they claim was blood, close to the girls’ dressing room on second floor. I couldn’t say whether it was blood or not. I deny that I ever said that my sister said she saw the negro on the box when she came out of the factory. He was sitting on a box between the elevator shaft and the staircase. That looks like my signature. I don’t know whether it is or not. Yes, I corrected certain statements in that paper.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

I went to Mr. Dorsey’s office because he subpoenaed me. I thought I had to obey it. Mr. Starnes and Mr. Campbell and the stenographer were there. All of them asked me questions. I signed a statement about twenty-one pages long. I have seen Jim Conley reading newspapers up on the fourth floor, twice since the murder. It is not unusual to see spots all over the metal room floor.

RE-CROSS EXAMINATION.

Conley was sitting by the elevator when he was reading those papers, during working hours. The other time he was reading down at the rear end of the building. It was an extra, but I don’t know what paper it was. I knew that he could write because I had seen him do it several times, with pen and ink. I don’t know whether he was making up his report of boxes, but I have seen him writing. Yes, I have seen spots along the route from the ladies’ closet to the elevator ever since I have been there. They have red varnish and red paint and such things like that that look like blood. I am sure there are spots all around in the metal room, but I won’t say they look like the spots near the ladies’ dressing room.

How jocular and playful Leo Max Frank was in the forenoon of April 26, 1913, apparently a man without a care in the world. Was he possibly even a man with the anticipated pleasure of a sexual tryst in mind? Contrast this with his nervousness and trembling and startling inability to perform everyday tasks when Newt Lee arrived at four in the afternoon — a time when, according to his story, he didn’t have any idea that Mary Phagan was dead and had nothing but a possible rain shower to worry about.

Factory employee Lemmie Quinn testified that he had been to the factory and glimpsed Frank in his office about 12:20, though he hadn’t mentioned that visit to anyone until days had passed — and even Frank failed to mention it until Quinn came forward. Quinn admitted that he had told Frank he “didn’t want to be brought into it,” but that he would mention the visit “if it would help.” He also confirmed the time of Miss Hall’s and Mrs. Freeman’s visit to the factory, but only indirectly, saying that he saw them in a nearby eatery, The Busy Bee, at around 12:30. He also claimed that “we have blood spots quite frequently” in the Metal Room.

Harry Denham, who was working on the fourth floor of the pencil factory the day of the killing, said that he saw Leo Frank around three and he did not appear especially anxious or nervous. If Jim Conley’s account is accurate, this would have been a time when Frank still might have been expecting Conley to return to “finish the job” — that is, burn the body. An hour later, when Newt Lee arrived, Frank would probably have realized that Conley had skipped out.

Minola McKnight, the Frank’s African-American cook, had earlier signed a statement saying that she had overheard a conversation between Frank and his wife in which Frank admitted to killing a girl earlier that day. Her statement was brought to the attention of the police by her husband. But she later denied her former statement, said her husband was lying, and that she had only signed the statement (even though her lawyer was present) because of a fear of jail and the detective’s “third degree” methods. Amid allegations that Mrs. Frank had suddenly started to give her money, both she and her husband stuck to their respective stories. If Minola McKnight was telling the truth the second time around and not the first, the Atlanta police were engaged in the crudest kind of abuse and subornation of perjury. Here is her testimony — the reader may assign whatever credibility he thinks it deserves:

MINOLA McKNIGHT (c[olored]), sworn for the Defendant.

I work for Mrs. Selig. I cook for her. Mr. and Mrs. Frank live with Mr. and Mrs. Selig. His wife is Mrs. Selig’s daughter. I cooked breakfast for the family on April 26th. Mr. Frank finished breakfast a little after seven o’clock. Mr. Frank came to dinner about 20 minutes after one that day. That was not the dinner hour, but Mrs. Frank and Mrs. Selig were going off on the two o’clock car. They were already eating when Mr. Frank came in. My husband, Albert McKnight, wasn’t in the kitchen that day between one and two o’clock at all. Standing in the kitchen door you can not see the mirror in the dining room. If you move up to the north end of the kitchen where you can see the mirror, you can’t see the dining room table. My husband wasn’t there all that day.

Mr. Frank left that day sometime after two o’clock. I next saw him at half past six at supper. I left about eight o’clock. Mr. Frank was still at home when I left. He took supper with the rest of the family. After this happened the detectives came out and arrested me and took me to Mr. Dorsey’s office, where Mr. Dorsey, my husband and another man were there. I was working at the Selig’s when they come and got me. They tried to get me to say that Mr. Frank would not allow his wife to sleep that night and that he told her to get up and get his gun and let him kill himself, and that he made her get out of bed. They had my husband there to bulldoze me, claiming that I had told him that. I had never told him anything of the kind. I told them right there in Mr. Dorsey’s office that it was a lie. Then they carried me down to the station house in the patrol wagon. They came to me for another statement about half past eleven or twelve o’clock that night and made me sign something before they turned me loose, but it wasn’t true. I signed it to get out of jail, because they said they would not let me out. It was all written out for me before they made me sign it.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I signed that statement (State’s Exhibit ” J “), but I didn’t tell you some of the things you got in there. I didn’t say he left home about three o’clock. I said somewhere about two. I did not say he was not there at one o’clock. Mr. Graves and Mr. Pickett, of Beck & Gregg Hardware Co., came down to see me. A detective took me to your (Mr. Dorsey’s) office. My husband was there and told me that I had told him certain things. Yes, I denied it. Yes, I wept and cried and stuck to it. When they first brought me out of jail, they said they did not want anything else but the truth, then they said I had to tell a lot of lies and I told them I would not do it. That man sitting right there (pointing to Mr. Campbell) and a whole lot of men wanted me to tell lies. They wanted me to witness to what my husband was saying. My husband tried to get me to tell lies. They made me sign that statement, but it was a lie. If Mr. Frank didn’t eat any dinner that day I ain’t sitting in this chair. Mrs. Selig never gave me no money. The statement that I signed is not the truth. They told me if I didn’t sign it they were going to keep me locked up. That man there (indicating) and that man made me sign it. Mr. Graves and Mr. Pickett made me sign it. They did not give me any more money after this thing happened. One week I was paid two weeks’ wages.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

None of the things in that statement is true. It’s all a lie. My wages never have been raised since this thing happened. They did not tell me to keep quiet. They always told me to tell the truth and it couldn’t hurt.

Mr. and Mrs. Selig, Frank’s in-laws. testified that Frank had acted normally on the day of the murder and the next day. A number of other witnesses, many of them Jewish, testified that they had seen Frank going to or coming back from lunch on April 26, a few adding that they saw no signs of nervousness as he made his way via the streetcar system.

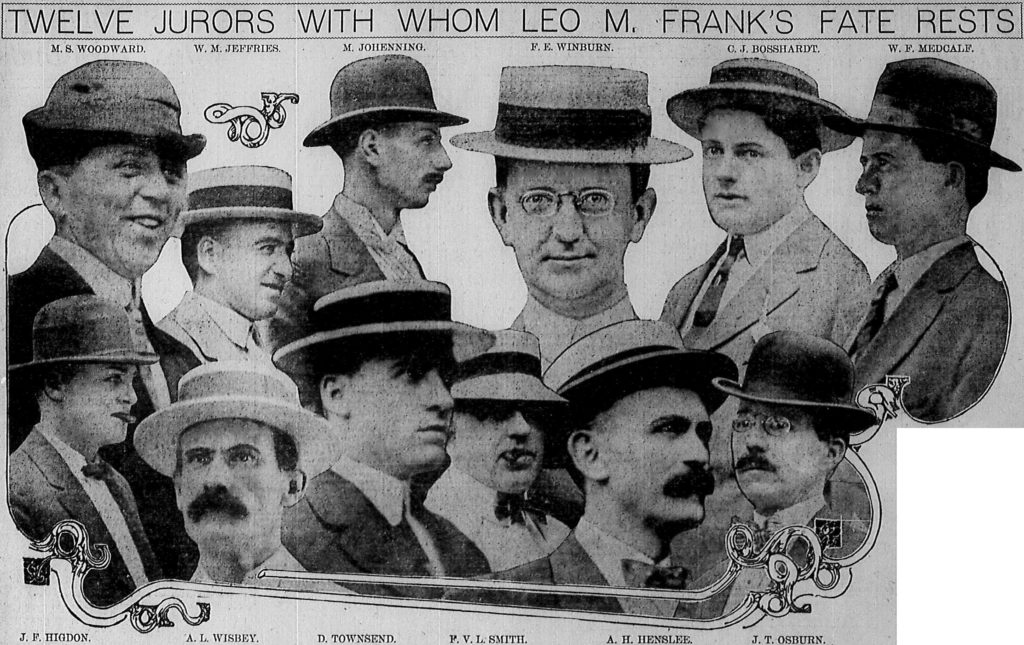

Several workers at the factory, testifying for the defense, said they’d never seen Leo Frank talking to Mary Phagan, that they’d never seen him with women in his office after hours, and that Conley’s reputation for veracity was bad. One of them, Iora Small, went further, volunteering for the benefit of the all-white jury that “I don’t know of any nigger on earth that I would believe on oath.” Miss Small, on cross-examination, stated that she and several of her co-workers had seen blood spots in the metal room the following Monday, near where the samples had been chipped up, “two or three spots, some the size of a nickle and some the size of a quarter.”

Several of Frank’s friends and family members said they dined or talked with Leo Frank the afternoon and evening the day after the murder, and that Frank hadn’t displayed any unusual nervousness then.

Frank’s lawyers showed audacity by bringing to the stand W.D. McWorth, the (later dismissed) Pinkerton man who had “discovered” what was insinuated to be a fragment of Mary Phagan’s pay envelope (showing the initials “M.P.”) and a “bloody club” on the first floor where Conley said he’d been stationed. The only hitch in this tale was that these “finds” were made almost three weeks after police and other Pinkerton agents had made a thorough search of the entire building.

The defense then brought numerous physicians to the stand who cast doubt on the time element of the case by claiming that Dr. Henry F. Harris’s autopsy analysis of the contents of Mary Phagan’s stomach was flawed, since it was difficult to gauge the degree of digestion of cabbage. Harris had said that Mary Phagan had met her death around 12:05 — about the same time Mary Phagan had come to collect her pay from Leo Frank and that Monteen Stover had found Leo Frank’s office — on the same floor as the Metal Room — utterly empty. But the jurors knew there was more than just cabbage in Mary Phagan’s last meal, and there was no trace of a living Mary anywhere in any witness’s testimony after her visit with Frank.

A number of friends and acquaintances of Frank were brought in to testify to Frank’s general good character. (Many consider this to be a tactical error on the defense’s part, since it opened the door for the prosecution to address Frank’s character — and several prosecution witnesses testified that Frank had made inappropriate sexual advances to girls and young women — an opportunity the prosecution would not otherwise have had. And the defense also chose not to cross-examine any of the young women who so testified, leaving an impression with the jurors that they dared not do so.)

One of the character witnesses for the defense had a surprise in store:

MISS IRENE JACKSON, sworn for the Defendant.

I worked at the pencil factory for three years. So far as I know Mr. Frank’s character was very well. I don’t know anything about him. He never said anything to me. I have never met Mr. Frank at any time for any immoral purpose.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I am the daughter of County Policeman Jackson. I never heard the girls say anything about him, except that they seemed to be afraid of him. They never would notice him at all. They would go to work when they saw him coming.

Miss Emily Mayfield and I were undressing in the dressing room once when Mr. Frank came to the door. He looked, turned around and walked out. He just came to the door and pushed it open. He smiled or made some kind of face. Miss Mayfield had her top dress off and had her old dress in her hand to put it on.

I told Mr. Darley I would not quit unless my father made me, and he said if the girls would stick to Frank they won’t lose anything.

I heard some remarks two or three times about Mr. Frank going to the dressing room on different occasions, but I don’t remember anything about it. The second time I heard of his going to the dressing room was when my sister was laying down there. She had her feet on a stool. She was dressed. I was in there at the time. He just walked in, and turned and walked out. Mr. Frank walked in the dressing room on Miss Mamie Kitchens, when I was in there. He never said anything the three times he walked in when I was there. The dressing room has a mirror and a few lockers for the foreladies. That’s the only thing that I have ever seen Mr. Frank do, go in the dressing room and stare at the girls. I have heard them speak of other times when I was not there.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

My father made me quit, after the murder. There are two windows in the dressing room opening on Forsyth Street. I think there had been some complaints of the girls flirting through the windows. I have heard of some of the girls flirting through the windows. The orders were against the girls flirting through the windows. Mr. Frank never came into the room at all, he pushed the door open and just looked. My sister and I were both dressed when Mr. Frank looked in the door. The other time he came in I was fixing to put on my street dress. I was not undressed.

RE-CROSS EXAMINATION.

I don’t know if Mr. Frank knew the girls were in there before he opened the door or not. It was the usual hour for them to be in there. He could have seen the girls register from the outer office, but not from the inner office. I have never heard any talk about Mr. Frank going around putting his hands on girls. I have never heard of his going out with any of the girls. My sister quit at the factory before Christmas. I have never flirted with anybody out of the window. I have heard them say that they didn’t want the girls to flirt around the factory. I have heard Mr. Frank say that to Miss McClellan, after she told him that she knew of some of the girls flirting.

Miss Jackson’s story lent credence, though not full corroboration, to the stories of Frank being very forward with the girls who worked under him. What ordinary male factory manager would fling open the door of a women’s dressing room, well knowing that it was, or might be, occupied?

___

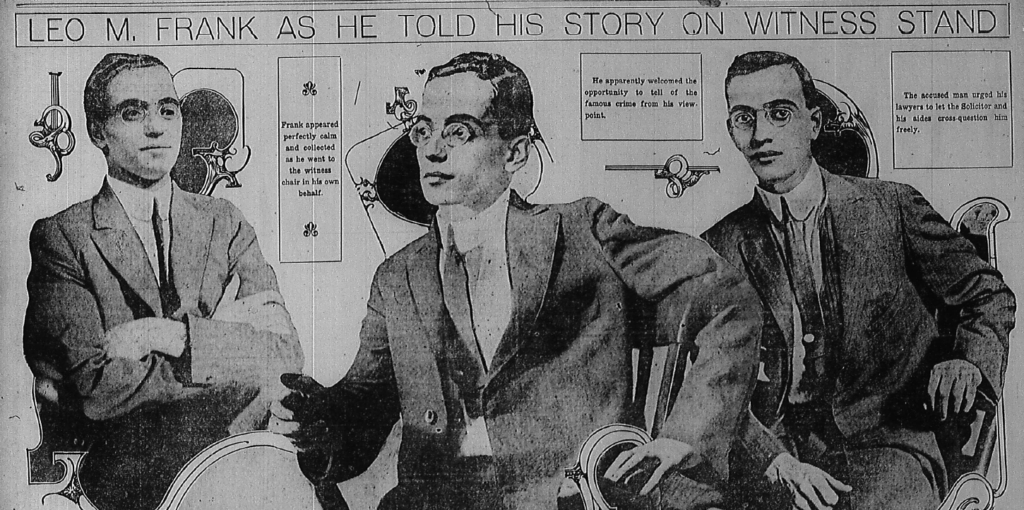

The most long-awaited moment of the entire trial had now arrived. On August 18, 1913 at 2:14 PM, the accused, Leo Max Frank, mounted the stand to speak to the jury in his own defense. And what a strange, amazing speech it was.

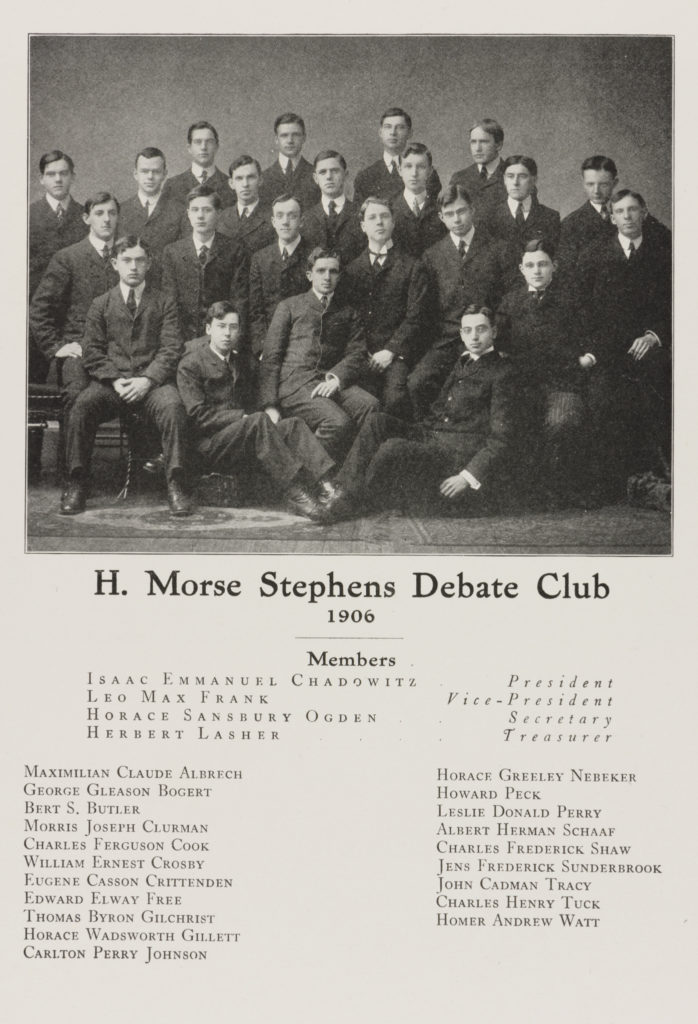

Under Georgia law, the defendant has a choice: he may remain silent, he may testify under oath in the customary way and be cross-examined by opposing counsel, or he may make an unsworn statement about which he may not be cross-examined. Amazingly, Leo Frank chose the last of these options. Here was Frank, proclaiming his innocence — Leo Frank, a skilled debater who had been a member of an Ivy League debate team — Leo Frank, with some of the best and toughest legal minds in the state on his side — here was this same Leo Frank quailing before a county prosecutor, refusing to be sworn, and refusing to be cross-examined. It gave the definite appearance of a man who dared not be cross-examined. Despite the near-certainty that such a choice would be a black mark in the eyes of the jury, Frank made that choice — and his platinum-plated legal team either agreed or acquiesced in his decision.

Weeks in preparation, Leo Frank’s unsworn speech was a mind-numbing nearly four hours long — and an astounding three of those four hours were devoted to recounting the minutiae of his office work on the day of the murder, mainly his financial entries and accounting book calculations, in excruciating detail. Frank even presented the original pages of the accounting book to the jury.

All this was Frank’s way of telling the jury that he simply hadn’t any time to spare that Saturday to ravish any 13-year-olds, or kill them, or cover up the crime. But how credible is that? At a little after noon, when Leo Frank was the last known person to have seen Mary Phagan alive, he had had three and a half hours to do his office work.

Both defense and prosecution agree that — guilty or innocent, whatever he may have done between noon and 1PM — he came back after lunch that day and had another three hours, from roughly 3PM to 6PM, to do whatever work needed to be done. Was his prolonged monologue supposed to convince his listeners that six and a half hours would not suffice for his calculations and that he definitely needed the noon hour too? If that were true, why had he originally planned to leave two entire hours early, at 4PM, to see a holiday baseball game with his brother-in-law? Wouldn’t that have made his accounting work impossible, too? And, if Leo Frank can do his accounting and other work in an average time of seven or eight hours, is it beyond belief that he could, if necessary, work 15% faster and give himself an hour or more to spare? In fact, who would ever know if he had just made up any missed work a day or two later?

Eventually, Frank would address issues more germane to the case in his statement:

Miss Hall left my office on her way home at this time, and to the best of my information there were in the building Arthur White and Harry Denham and Arthur White’s wife on the top floor. To the best of my knowledge, it must have been from ten to fifteen minutes after Miss Hall left my office, when this little girl, whom I afterwards found to be Mary Phagan, entered my office and asked for her pay envelope. I asked for her number and she told me; I went to the cash box and took her envelope out and handed it to her, identifying the envelope by the number.

Again, Frank is here sticking to his story about not knowing Mary Phagan by name. It would have been more believable if he had at long last admitted that fear of being accused of murder and worse had frightened him into a lie. It might have given the jury the impression of a man in difficult circumstances finally coming clean.

The assertion that Frank never knew Mary Phagan’s name approaches the preposterous. Frank controlled the payroll and entered the amounts in his accounting books every week. We know that he wrote, in his own hand, Mary Phagan’s initials “M.P.” next to her employee number and pay amount in these books every week for the full 52 weeks of Mary Phagan’s employment at the National Pencil Company. How would he know her initials if he did not know her name?

We know from the blueprints of the factory that the only bathroom on the second floor, where Frank’s office was located, was the Metal Room bathroom. Mary Phagan worked in the Metal Room. To get to this bathroom, Frank, a regular coffee drinker, had to pass right by Mary Phagan’s work station. The employees worked 11-hour days, five days a week, 52 weeks a year. That’s at least 2,860 hours during the slightly over one year that little Mary had worked for Frank. Even if he only used the bathroom once in every three hours, that’s over 953 times that Leo Frank would have walked right by Mary Phagan. And, considering the testimony of other girls and young women who worked there that he did speak to them on occasion — it seems wildly unlikely that he would know none of them by name. And if he knew any of them by name, it stands to good reason that one that he knew would be Mary Phagan, who worked near his office and not more than three feet — closer than any other employee — from the door to the bathroom that he used multiple times, practically brushing up against her, every day. (One wishes that prosecutor Dorsey had asked every second-floor employee if Leo M. Frank knew him or her by name. Frank, in his statement, does make mention of quite a few female employees by name, and, early in the investigation, he suggested that J.M. Gantt was friendly with Mary — a thing he was hardly likely to know if he didn’t have some acquaintance with her.)

Frank continued his unsworn statement:

She [Mary Phagan — Ed.] left my office and apparently had gotten as far as the door from my office leading to the outer office, when she evidently stopped and asked me if the metal had arrived, and I told her no. She continued on her way out, and I heard the sound of her footsteps as she went away. It was a few moments after she asked me this question that I had an impression of a female voice saying something; I don’t know which way it came from; just passed away and I had that impression.

This was different from what Frank had said shortly after the murder story broke. Then he had said that he heard Mary talking to another girl — a girl who has never turned up, probably because she didn’t exist. Frank had said: “She went out through the outer office and I heard her talking with another girl.” Every person known to be in the vicinity was extensively investigated and interviewed, and no girl was discovered who spoke to Mary Phagan or met her at that time. Monteen Stover, who thought highly of Frank and had no reason to hurt him, was the only other girl there, and she testified that she saw only an empty office — no Mary Phagan, no Leo Frank.

Frank’s unsworn statement continues:

This little girl had evidently worked in the metal department by her question and had been laid off owing to the fact that some metal that had been ordered had not arrived at the factory; hence, her question. I only recognized this little girl from having seen her around the plant and did not know her name, simply identifying her envelope from her having called her number to me.

Leo Frank actually had the gall to say that Mary Phagan “had evidently worked in the metal department by her question,” implying that not only did he not know the dead girl by name, but did not know her by sight either, at least not enough to know she worked in the metal department, something he only inferred from her question! This is so beyond the bounds of probability that it can hardly be believed, and casts serious doubt on everything Leo Frank said about this case. It’s enough by itself to make one think that Leo Frank is hiding something, something very dark, about his relationship with this girl.

In his unsworn statement above, Frank says that when Mary started to leave his office, “she evidently stopped and asked me if the metal had arrived, and I told her no.” [Emphasis mine.]

It was a matter of controversy whether Frank had actually answered “no” or had instead said “I don’t know” — detectives claimed that Frank had admitted to answering “I don’t know” when he was first questioned. If it was indeed “I don’t know,” it might have been an opening for Frank to have invited Mary Phagan to “go and check” and accompany him to the Metal Room to “see if the metal had arrived.” And the Metal Room was precisely where the prosecution, the police — and even the investigators hired by the pencil company — contended the murder had taken place.

And then Leo Frank made the most startling admission of all — possibly, short of a detailed and abject confession, the most startling admission he could possibly make:

Now, gentlemen, to the best of my recollection from the time the whistle blew for twelve o’clock until after a quarter to one when I went up stairs and spoke to Arthur White and Harry Denham, to the best of my recollection, I did not stir out of the inner office; but it is possible that in order to answer a call of nature or to urinate I may have gone to the toilet. Those are things that a man does unconsciously and cannot tell how many times nor when he does it. Now, sitting in my office at my desk, it is impossible for me to see out into the outer hall when the safe door is open, as it was that morning, and not only is it impossible for me to see out, but it is impossible for people to see in and see me there.

Frank was evidently hoping to blunt the effect of Monteen Stover’s testimony, explaining why she may have found his office empty from 12:05 to 12:10 by saying perhaps he’d gone to use the toilet, or been hidden behind the safe door, when she came in. The “safe door” argument was a weak one, as a young lady earnestly seeking her pay was likely to simply glance around its open door — even if Frank had been precisely positioned behind it. So — after months of denying he’d left his office at all between 12 and 12:45 — he stated that he might have have left it to “unconsciously” visit the bathroom.

And what bathroom would he have used? The only bathroom on the second floor — where Frank’s office was located — was the Metal Room bathroom. Frank was suggesting that he may have been using the bathroom — the Metal Room bathroom! — when Monteen Stover found his office empty, at the precise time when the evidence indicates Mary Phagan was being murdered in that very location. This was also astounding because a few weeks earlier Leo Frank had emphatically told the coroner’s jury that on the day of the murder he had not used the bathroom all day long, a statement so insistent and so ridiculous that it made more than a few eyebrows rise at the time. What is it about that bathroom that seems to unnerve Leo Frank, and make him stumble and contradict himself so much?

And now this new admission: Frank was admitting that he might have gone to the Metal Room, where strands of hair that looked like Mary Phagan’s had been found on a lathe handle — hair that hadn’t been there the Friday before — and where a five-inch fan-sized blood stain had been found the following Monday. The stain was clumsily concealed with a layer of white Haskoline powder which had soaked the blood up and turned pink — a condition that certainly wouldn’t have endured for even a single week of factory work and traffic, ruling out the defense’s argument that the stain was very old.

Frank was admitting that he might have used the Metal Room bathroom, exactly where Conley said he found the battered, strangled, and lifeless body of Mary Phagan — where he said he wrapped her body in a sack and prepared to carry it, with Leo Frank’s help, to the basement, dropping it at one point in the passageway, where another blood stain was subsequently found.

He was telling the jurors who were to decide his fate that he may indeed have been at the precise location at the precise time when Mary Phagan had been murdered according to the prosecution’s witnesses. And this after maintaining for months that he had never made such a visit, or in fact left his office for even an instant from 12 to 12:45!

Frank went on to say in his statement that, after he returned home for lunch:

I sat down to my dinner and before I had taken anything, I turned in my chair to the telephone, which is right behind me and called up my brother-in-law to tell him that on account of some work I had to do at the factory, I would be unable to go with him, he having invited me to go with him out to the ball game. I succeeded in getting his residence and his cook answered the phone and told me that Mr. Ursenbach had not come back home. I told her to give him a message for me, that I would be unable to go with him.

So, supposedly, Frank could not attend the ball game “on account of some work I had to do at the factory.” In previous statements Frank had said he’d changed his mind because of impending rain — why the change? And why would meticulous Leo Frank, so knowledgeable of how long his endless financial calculations took him, have planned leaving hours early, at 4PM, unless he knew for sure he’d be done by then? And if he wasn’t able to be done by then, necessitating the cancellation, what unforeseen event had intervened and taken up his time?

Frank went on with his courtroom statement:

Then that other insinuation, an insinuation that is dastardly that it is beyond the appreciation of a human being, that is, that my wife didn’t visit me; now the truth of the matter is this, that on April 29th, the date I was taken in custody at police headquarters, my wife was there to see me, she was downstairs on the first floor; I was up on the top floor. She was there almost in hysterics, having been brought there by her two brothers-in-law, and her father. Rabbi Marx was with me at the time. I consulted with him as to the advisability of allowing my dear wife to come up to the top floor to see me in those surroundings with city detectives, reporters and snapshotters; I thought I would save her that humiliation and that harsh sight, because I expected any day to be turned loose and be returned once more to her side at home. Gentlemen, we did all we could do to restrain her in the first days when I was down at the jail from coming on alone down to the jail, but she was perfectly willing to even be locked up with me and share my incarceration.

Mrs. Frank did not visit her husband for 13 days after his arrest — an act that could possibly be explained by her outrage at her husband’s putative infidelity — and Frank’s claim that she had to be “restrained” from actually moving into his cell is too extreme to be credible, especially since no reports are extant of her having attempted to see him again in those first days, to say nothing of taking up residence in his lockup. Remember, Minola McKnight had stated that Leo Frank confessed to killing a girl to his wife the night of the murder — though she later repudiated her statement. Was the box of candy purchased on the way home by Leo Frank that evening an attempt to reassure her of his love despite what he had done? Was her anger so extreme she shunned him for almost two weeks in his hour of need, or did she really have to be forced to stay away just to “save her that humiliation” of seeing him with detectives, reporters, and photographers?

Lucille Selig Frank did eventually become the dutiful wife by the side of her accused husband, and did well in that role. But that didn’t happen immediately.

Upon her death decades later it was discovered that she left explicit instructions — not that she be buried in Queens, New York by her husband’ side — but that she be cremated and her ashes scattered in a public park.

Frank continued his statement:

Gentlemen, I know nothing whatever of the death of little Mary Phagan. I had no part in causing her death nor do I know how she came to her death after she took her money and left my office. I never even saw Conley in the factory or anywhere else on that date, April 26, 1913. The statement of the witness Dalton is utterly false as far as coming to my office and being introduced to me by the woman Daisy Hopkins is concerned. If Dalton was ever in the factory building with any woman, I didn’t know it. I never saw Dalton in my life to know him until this crime.

One amazing fact that this reporter has uncovered is that the Atlanta Constitution and the Atlanta Georgian (the Georgian by this time was taking an editorial line favorable to Frank) completely omitted Leo Frank’s “unconscious bathroom visit” admission when they printed Frank’s full statement on August 18, 1913 and August 19, 1913. The Atlanta Journal did include the admission, so it seems unlikely that the words “call of nature” or “urinate” were deemed too shocking for a public reading about a brutal strangulation murder.

We’ll continue with the final installment of The Leo Frank Trial next week right here at The American Mercury, when I’ll be examining the claims that anti-Semitism was the motive for Frank’s prosecution and conviction, and much more.