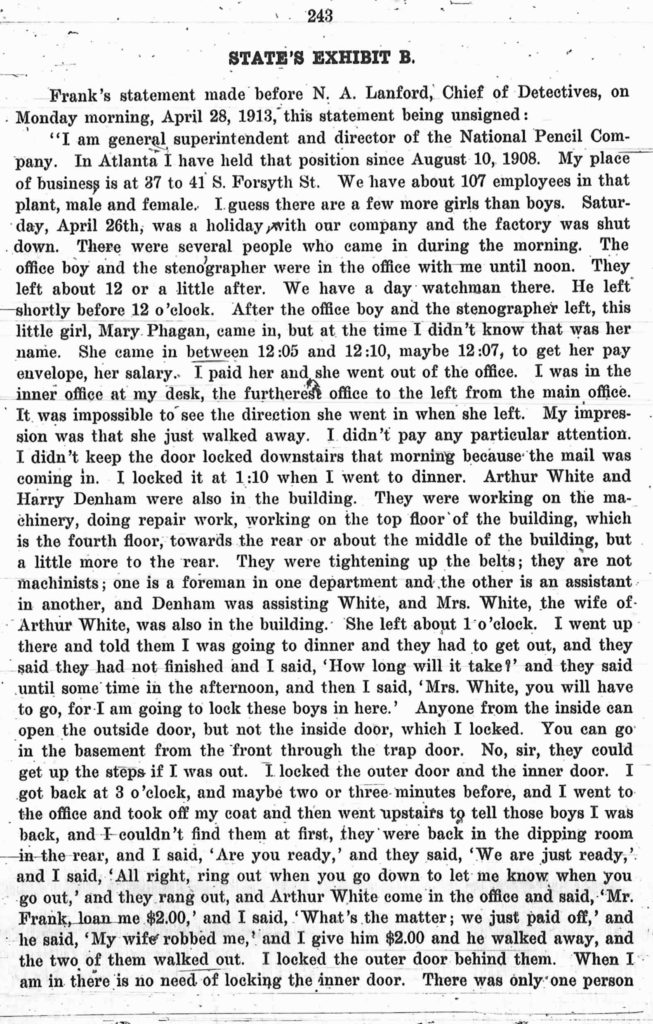

Join The American Mercury as we recount the events of the final week of the trial of Leo Frank (pictured) for the slaying of Mary Phagan.

by Bradford L. Huie

ON THE HEELS of Leo Frank’s astounding unsworn statement to the court, the defense called a number of women who stated that they had never experienced any improper sexual advances on the part of Frank. But the prosecution rebutted that testimony with several rather persuasive female witnesses of its own. These rebuttal witnesses also addressed Frank’s claims that he was so unfamiliar with Mary Phagan that he did not even know her by name. (For background on this case, read our introductory article, our coverage of Week One, Week Two, and Week Three of the trial, and my exclusive summary of the evidence against Frank.)

Here are the witnesses’ statements, direct from the Brief of Evidence, interspersed with my commentary. The emphasis and paragraphing (for clarity) is mine. The defense recommenced with a large contingent of Frank’s friends, business associates, and employees who would say that Leo Frank was of good character and had not, to their knowledge, made any improper sexual approaches to the girls and women who worked under him:

MISS EMILY MAYFIELD, sworn for the Defendant.

I worked at the pencil factory last year during the summer of 1912. I have never been in the dressing room when Mr. Frank would come in and look at anybody that was undressing.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I work at Jacobs’ Pharmacy. My sister used to work at the pencil factory. I don’t remember any occasion when Mr. Frank came in the dressing room door while Miss Irene Jackson and her sister were there.

MISSES ANNIE OSBORNE, REBECCA CARSON, MAUDE WRIGHT, and MRS. ELLA THOMAS, all sworn for the Defendant, testified that they were employees of the National Pencil Company; that Mr. Frank’s general character was good; that Conley’s general character for truth and veracity was bad and that they would not believe him on oath.

MISSES MOLLIE BLAIR, ETHEL STEWART, CORA COWAN, B. D. SMITH, LIZZIE WORD, BESSIE WHITE, GRACE ATHERTON, and MRS. BARNES, all sworn for the Defendant, testified that they were employees of the National Pencil Company, and work on the fourth floor of the factory; that the general character of Leo. M. Frank was good; that they have never gone with him at any time or place for any immoral purpose, and that they have never heard of his doing anything wrong.

MISSES CORINTHIA HALL, ANNIE HOWELL, LILLIE M. GOODMAN, VELMA HAYES, JENNIE MAYFIELD, IDA HOLMES, WILLIE HATCHETT, MARY HATCHETT, MINNIE SMITH, MARJORIE McCORD, LENA McMURTY, MRS. W. R. JOHNSON, MRS. S. A. WILSON, MRS. GEORGIA DENHAM, MRS. O. JONES, MISS ZILLA SPIVEY, CHARLES LEE, N. V. DARLEY, F. ZIGANKI, and A. C. HOLLOWAY, MINNIE FOSTER, all sworn for the Defendant, testified that they were employees of the National Pencil Company and knew Leo M. Frank, and that his general character was good.

D. I. MacINTYRE, B. WILDAUER, MRS. DAN KLEIN, ALEX DITTLER, DR. J.E. SOMMERFIELD, F. G. SCHIFF, AL. GUTHMAN, JOSEPH GERSHON, P.D. McCARLEY, MRS. M. W. MEYER, MRS. DAVID MARX, MRS. A. I. HARRIS, M. S. RICE, L. H. MOSS, MRS. L.H. MOSS, MRS. JOSEPH BROWN, E.E. FITZPATRICK, EMIL DITTLER, WM. BAUER, MISS HELEN LOEB, AL. FOX, MRS. MARTIN MAY, JULIAN V. BOEHM, MRS. MOLLIE ROSENBERG, M.H. SILVERMAN, MRS. L. STERNE, CHAS. ADLER, MRS. R.A. SONN, MISS RAY KLEIN, A.J. JONES, L. EINSTEIN, J. BERNARD, J. FOX, MARCUS LOEB, FRED HEILBRON, MILTON KLEIN, NATHAN COPLAN, MRS. J. E. SOMMERFIELD, all sworn for the Defendant, testified that they were residents of the city of Atlanta, and have known Leo M. Frank ever since he has lived in Atlanta; that his general character is good.

MRS. M. W. CARSON, MARY PIRK, MRS. DORA SMALL, MISS JULIA FUSS, R.P. BUTLER, JOE STELKER, all sworn for the Defendant, testified that they were employees of the National Pencil Com- pany; that they knew Leo M. Frank and that his general character is good.

The character issue having been broached by the defense, the door was opened to the prosecution to bring forth witnesses on the same subject:

MISS MYRTIE CATO, MAGGIE GRIFFIN, MRS. C.D. DONEGAN, MRS. H. R. JOHNSON, MISS MARIE CARST, MISS NELLIE PETTIS, MARY DAVIS, MRS. MARY E. WALLACE, ESTELLE WINKLE, CARRIE SMITH, all sworn for the Defendant [sic — This is a typographical error; these witnesses were sworn for the State. — Ed.], testified that they were formerly employed at the National Pencil Company and worked at the factory for a period varying from three days to three and a half years; that Leo M. Frank’s character for lasciviousness was bad.

The defense — ominously — chose not to cross-examine any of these witnesses. This restricted the prosecution to the mere statements that Frank had a “bad character for lasciviousness”: Under the rules of the court, Dorsey could only ask for particulars — could only inquire into why Frank had such a bad character — if the defense opened the door with cross-examination. This the defense refused to do — with any of the ten women who said that Frank was badly lascivious. The jury was thus left with the impression that the defense dared not do so — a point that would be hammered home in the prosecution’s closing statement.

Two of these witnesses had made far more extensive statements at the Coroner’s Inquest, where the rules of evidence permit wider latitude in questioning. As I reported in an earlier article:

Several young women and girls testified at the inquest that Frank had made improper advances toward them, in one instance touching a girl’s breast and in another appearing to offer money for compliance with his desires.

The Atlanta Georgian reported: “Girls and women were called to the stand to testify that they had been employed at the factory or had had occasion to go there, and that Frank had attempted familiarities with them. Nellie Pettis, of 9 Oliver Street, declared that Frank had made improper advances to her.

“She was asked if she had ever been employed at the pencil factory. No, she answered.

“Q: Do you know Leo Frank? A: I have seen him once or twice.

“Q: When and where did you see him? A: In his office at the factory whenever I went to draw my sister-in-law’s pay.

“Q: What did he say to you that might have been improper on any of these visits? A: He didn’t exactly say — he made gestures. I went to get sister’s pay about four weeks ago and when I went into the office of Mr. Frank I asked for her. He told me I couldn’t see her unless ‘I saw him first.’ I told him I didn’t want to ‘see him.’ He pulled a box from his desk. It had a lot of money in it. He looked at it significantly and then looked at me. When he looked at me, he winked. As he winked he said: ‘How about it?’ I instantly told him I was a nice girl.

“Here the witness stopped her statement. Coroner Donehoo asked her sharply: ‘Didn’t you say anything else?’ ‘Yes, I did! I told him to go to h–l! and walked out of his office.’” (Atlanta Georgian, May 9, 1913, “Phagan Case to be Rushed to Grand Jury by Dorsey”)

If true, this was shocking behavior on Frank’s part. Not only was he importuning a young woman for illicit relations in exchange for money, but it was a woman he’d only seen once or twice. If he would act in such a way with an absolute stranger, what wouldn’t he do? In the same article, another young girl testified to Frank’s pattern of improper familiarities:

“Nellie Wood, a young girl, testified as follows:

“Q: Do you know Leo Frank? A: I worked for him two days.

“Q: Did you observe any misconduct on his part?

“A: Well, his actions didn’t suit me. He’d come around and put his hands on me when such conduct was entirely uncalled for.

“Q: Is that all he did? A: No. He asked me one day to come into his office, saying that he wanted to talk to me. He tried to close the door but I wouldn’t let him. He got too familiar by getting so close to me. He also put his hands on me.

“Q: Where did he put his hands? He barely touched my breast. He was subtle in his approaches, and tried to pretend that he was joking. But I was too wary for such as that.

“Q: Did he try further familiarities? A: Yes.”

The trial testimony continued:

MISS MAMIE KITCHENS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I have worked at the National Pencil Company two years. I am on the fourth floor. I have not been called by the defense. Miss Jones and Miss Howard have also not been called by the defense to testify. I was in the dressing room with Miss Irene Jackson when she was undressed. Mr. Frank opened the door, stuck his head inside. He did not knock. He just stood there and laughed. Miss Jackson said, “Well, we are dressing, blame it,” and then he shut the door.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

Yes, he asked us if we didn’t have any work to do. It was during business hours. We didn’t have any work to do. We were going to leave. I have never met Mr. Frank anywhere, or any time for any immoral purposes.

MISS RUTH ROBINSON, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I have seen Leo M. Frank talking to Mary Phagan. He was talking to her about her work, not very often. He would just tell her, while she was at work, about her work. He would stand just close enough to her to tell her about her work. He would show her how to put rubbers in the pencils. He would just take up the pencil and show her how to do it. That’s all I saw him do. I heard him speak to her; he called her Mary. That was last summer.

MISS DEWEY HEWELL, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I stay in the Home of the Good Shepherd in Cincinnati. I worked at the pencil factory four months. I quit in March, 1913. I have seen Mr. Frank talk to Mary Phagan two or three times a day in the metal department. I have seen him hold his hand on her shoulder. He called her Mary. He would stand pretty close to her. He would lean over in her face.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

All the rest of the girls were there when he talked to her. I don’t know what he was talking to her about.

MISS REBECCA CARSON, re-called by the State in rebuttal.

I have never gone into the dressing room on the fourth floor with Leo M. Frank.

MISS MYRTICE CATO, MISS MAGGIE GRIFFIN, both sworn for the State, testified that they had seen Miss Rebecca Carson go into the ladies’ dressing room on the fourth floor with Leo M. Frank two or three times during working hours; that there were other ladies working on the fourth floor at the time this happened.

J. E. DUFFY, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I worked at the National Pencil Company. I was hurt there in the metal department. I was cut on my forefingers on the left hand. That is the cut right around there (indicating). It never cut off any of my fingers. I went to the office to have it dressed. It was bleeding pretty freely. A few drops of blood dropped on the floor at the machine where I was hurt. The blood did not drop anywhere else except at that machine. None of it dropped near the ladies’ dressing room, or the water cooler. I had a large piece of cotton wrapped around my finger. When I was first cut I just slapped a piece of cotton waste on my hand.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I never saw any blood anywhere except at the machine. I went from the office to the Atlanta Hospital to have my finger attended to.

W. E. TURNER, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I worked at the National Pencil Company during March of this year. I saw Leo Frank talking to Mary Phagan on the second floor, about the middle of March. It was just before dinner. There was nobody else in the room then. She was going to work and he stopped to talk to her. She told him she had to go to work. He told her that he was the superintendent of the factory, and that he wanted to talk to her, and she said she had to go to work. She backed off and he went on towards her talking to her. The last thing I heard him say was he wanted to talk to her. That is all I saw or heard.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

That was just before dinner. The girls were up there getting ready for dinner. Mary was going in the direction where she worked, and Mr. Frank was going the other way. I don’t know whether any of the girls were still at work or not. I didn’t look for them. Some of the girls came in there while this was going on and told me where to put the pencils. Lemmie Quinn’s office is right there. I don’t know whether the girls saw him talking to Mary or not, they were in there. It was just before the whistle blew at noon. Mr. Frank told her he wanted to speak to her and she said she had to go to work, and the girls came in there while this conversation was going on. I can’t describe Mary Phagan. I don’t know any of the other little girls in there. I don’t remember who called her Mary Phagan, a young man on the fourth floor told me her name was Mary Phagan. I don’t know who he was. I didn’t know anybody in the factory. I can’t describe any of the girls. I don’t know a single one in the factory.

The defense had made an impression with their parade of young female pencil factory workers who not only had never been on the receiving end of any importunities by Leo Frank, but who had never seen Frank speaking to Mary Phagan. Almost all of these were still employed by the firm, which was supporting Frank — and had motive to protect their source of income, of course. But, financial motives aside, it still would be quite surprising for even the most lecherous boss imaginable, in charge of dozens and dozens of young women and girls, to have attempted to seduce every single one! So finding a large number who had never been approached sexually by Frank could hardly be seen as definitive proof that he had never done so. Nor would it seem likely, assuming that Leo Frank had talked to Mary Phagan on a number of occasions, that every single employee, or even a majority of them, would have seen such conversations. So finding quite a number who had never witnessed such conversations meant little.

But finding some who had witnessed questionable forays by Frank into the ladies’ dressing room — and who had been sexually approached by Frank or witnessed his approaches to others — and who had seen Frank talk to Mary Phagan, addressing her by name — was enough to almost entirely destroy the character edifice built up by the defense of a Leo Frank who didn’t know Mary Phagan and whose behavior toward his female employees was above reproach. Most damaging of all was what it did to Leo Frank’s reputation for truthfulness.

After a motorman named Merk testified that defense witness Daisy Hopkins had a reputation as a liar, George Gordon, Minola McKnight’s attorney, testified as to the events of the night that Minola McKnight made her sensational affidavit claiming that Leo Frank had admitted to his wife that he wanted to die because he had killed a girl that day. McKnight, who worked for the Franks as a cook, had since repudiated the affidavit and was claiming it was obtained from her by force.

GEORGE GORDON, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am a practicing lawyer. I was at police station part of the time when Minola McKnight was making her statement. I was outside of the door most of the time. I went down there with habeas corpus proceedings to have her sign the affidavit and when I got there the detectives informed me that she was in the room, and I sat down and waited outside for her two hours, and people went in and out of the door, and after I had waited there I saw the stenographer of the recorder’s court going into the room and I decided I had better make a demand to go into the room, which I did, and I was then allowed to go into the room and I found Mr. Febuary reading over to her some stenographic statement he had taken.

There were two other men from Beck & Gregg Hardware store and Pat Campbell and Mr. Starnes and Albert McKnight. After that was read Mr. Febuary went out to write it off on the typewriter and while he was out Mr. Starnes said, “Now this must be kept very quiet and nobody be told anything about this.” I thought it was agreed that we would say nothing about it. I was surprised when I saw it in the newspapers two or three days afterwards.

I said to Starnes: “There is no reason why you should hold this woman, you should let her go.” He said he would do nothing without consulting Mr. Dorsey and he suggested that I had better go to Mr. Dorsey’s office. I went to his office and he called up Mr. Starnes and then I went back to the police station and told Starnes to call Mr. Dorsey and I presume that Mr. Dorsey told him to let her go. Anyway he said she could go. You (Mr. Dorsey) said you would let her go also. That morning you had said you would not unless I took out a habeas corpus. In the morning after Chief Beavers told me he would not let her go on bond and unless you (Mr. Dorsey) would let her go, I went to your office and told you that she was being held illegally and you admitted it to me and I said we would give bond in any sum that you might ask. You said you would not let her go because you would get in bad with the detectives, and you advised me to take out a habeas corpus, which I did. The detectives said they couldn’t let her got without your consent. You said you didn’t have anything to do with locking her up.

As to whether Minola McKnight did not sign this paper freely and voluntarily (State’s Exhibit J), it was signed in my absence while I was at [the] police station. When I came back this paper was lying on the table signed. That paper is substantially the notes that Mr. Febuary read over to her. As they read it over to her, she said it was about that way.

Yes, you agreed with me that you had no right to lock her up. I don’t know that you said you didn’t do it. I don’t remember that we discussed that. You told me that you would not direct her to be let loose, because you would get in bad with the detectives. I had told you that the detectives told me they would not release her unless you said so. I took out a habeas corpus immediately afterwards and went down there to get her released, and she was released.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I heard that they had had her in Mr. Dorsey ‘s office and she went away screaming and was locked up. I knew that Mr. Dorsey was letting this be done. She was locked in a cell at the police station when I saw her. They admitted that they did not have any warrant for her arrest. Beavers said he would not let her out on bond unless Mr. Dorsey said so. He said the charge against her was suspicion. They put her in a cell and kept her until four o’clock the next day before they let her go. When I went down to see her in the cell, she was crying and going on and almost hysterical. When I asked Mr. Dorsey to let her go out on bond, he said he wouldn’t do it because he would get in bad with the detectives, but that if I would let her stay down there with Starnes and Campbell for a day, he would let her loose without any bond, and I said I wouldn’t do it. I said that I considered it a very reprehensible thing to lock up somebody because they knew something, and he said, “Well, it is sometimes necessary to get information,” and I said, “Certainly our liberty is more necessary than any information, and I consider it a trampling on our Anglo-Saxon liberties.” They did not tell me that they already had a statement that she had made, and which she declared to be the truth.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

You (Mr. Dorsey) did not tell me that you had no right to lock anybody up. I told you that, and you agreed to it, but you would not let her go. I told you that Chief Beavers said he would do what you said and then I asked you to give me an order. You said you wouldn’t give me an order. When I told Starnes that I thought I ought to be in that room while Minola was making the statement, he knocked on the door, and it was unlocked on the inside and they let me in. They let me into the room at once after I had been sitting there two hours. I was present when she made the statement about the payment of the cook. I don’t remember what questions I asked her at that time. I was her attorney. I didn’t go down there to examine her; I went there to get her out. Starnes and Campbell were in and out of the room during the time. Mr. Starnes stayed on the outside of the door part of the time. I don’t know who was in the room and who was not while I was outside.

Next on the stand was Albert McKnight, Minola’s husband, whose testimony about the lunch hour at the Franks on the day of the murder had been attacked by the defense. Frank’s lawyers had used a diagram of the household to show that he could not have seen what he claimed to have seen. McKnight testified that the diagram was inaccurate and did not show the furniture in its true positions on April 26.

Following Albert McKnight were his employers, who also shed some light on Minola’s statement. They had been present while she was being held, and had even gotten her to make statements to them while detectives were not present. These statements were consistent with her affidavit, and not consistent with her later denial of it:

R. L. CRAVEN, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am connected with the Beck and Gregg Hardware Co. Albert McKnight also works for the same company. He asked me to go down and see if I could get Minola McKnight out when she was arrested. I went there for that purpose. I was present when she signed that affidavit (State’s Exhibit J).

I went out with Mr. Pickett to Minola McKnight ‘s home the latter part of May. Albert McKnight was there. On the 3rd day of June, we were down at the station house and they brought Minola McKnight in and we questioned her first as to the statements Albert had given me; at first she would not talk, she said she didn’t know anything about it.

I told her that Albert made the statement that he was there Saturday when Mr. Frank came home, and he said Mr. Frank came in the dining room and stayed about ten minutes and went to the sideboard and caught a car in about ten minutes after he first arrived there, and I went on and told her that Albert had said that Minola had overheard Mrs. Frank tell Mrs. Selig that Mr. Frank didn’t rest well and he came home drinking and made Mrs. Frank get out of bed and sleep on a rug by the side of the bed and wanted her to give him his pistol to shoot his head off and that he had murdered somebody, or something like that. Minola at first hesitated, but finally she told everything that was in that affidavit. When she did that Mr. Starnes, Mr. Campbell, Mr. Febuary, Albert McKnight, Mr. Pickett, and Mr. Gordon were there. When we were questioning her, I don’t remember whether anybody but Mr. Pickett and myself and Albert McKnight were there.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

We went down there about 11:30 o’clock. I didn’t know that she had been in jail twelve hours then. I suppose she was in jail because they needed her as a witness. I was in Mr. Dorsey’s office only one time about this matter, the same morning I started out to see if I could get her and I went to see Mr. Dorsey about getting her out. Her husband wanted her out of jail and I went to see Mr. Dorsey about getting her out.

At first she denied it. I questioned her for something like two hours. I didn’t know she had already made a statement about the truth of the transaction. Mr. Dorsey didn’t read it to me. He said she was hysterical and wouldn’t talk at all. I went down to get her to make some kind of a statement; I wanted her to tell the truth in the matter. I wanted to see whether her husband was telling the truth or whether she was telling a falsehood.

Yes, she finally made a statement that agreed with her husband, and I left after awhile.

As to why I didn’t stay and get her out, because I didn’t want to. I went after we got her statement. No, I didn’t get her out of jail. I did not look after her any further than that. I don’t think Mr. Dorsey told me to question her. He wanted me to go out to see her. He said Mr. Starnes and Mr. Campbell would be up there and they would let us know about it, and we went up there and Mr. Starnes and Mr. Campbell brought her in. They let us see her all right. I did not ask Campbell or Starnes to turn her out. I didn’t ask anybody to turn her out. I never made any suggestion to anybody about turning her out. Nobody cursed, mistreated or threatened this woman while I was there. I don’t know what took place before I got there.

E. H. PICKETT, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I work at Beck & Gregg Hdw. Co. I was present when that paper was signed (State’s Exhibit J) by Minola McKnight. Albert McKnight, Starnes, Campbell, Mr. Craven, Mr. Gordon was present when she made that statement.

We questioned her about the statement Albert had made and she denied it all at first. She said she had been cautioned not to talk about this affair by Mrs. Frank or Mrs. Selig. She stated that Albert had lied in what he told us. She finally began to weaken on one or two points and admitted that she had been paid a little more money than was ordinarily due her.

There was a good many things in that statement that she did not tell us, though, at first. She didn’t tell us all of that when she went at it. She seemed hysterical at the beginning. We told her that we weren’t there to get her into trouble, but came down there to get her out, and then she agreed to talk to us but would not talk to the detectives. The detectives then retired from the room.

Albert told her that she knew she told him those things. She denied it, but finally acknowledged that she said a few of those things, and among the things I remember is that she was cautioned not to repeat anything that she heard. We asked her a thousand questions perhaps. I don’t know how many. I called the detectives and told them we had gotten all the admissions we could. We didn’t have any stenographer and Mr. Craven began writing it out, and Mr. Craven had written only a small portion when the stenographer came.

She did not make all of that statement in the first talk she had with us. She didn’t say anything with reference to Mrs. Frank having stated anything to her mother on Sunday morning.

The affidavit does not contain anything that she did not state there that day. Before she made that affidavit, she said he did eat dinner that day. She finally said he didn’t eat any. At first she said he remained at home at dinner time about half an hour or more. She finally said he only remained about ten minutes. At first she said Albert McKnight was not there that day. She finally said he was there. She said she was instructed not to talk at first. At first she said her wages hadn’t been changed, finally said her wages had been raised by the Seligs. As to what, if anything, she said about a hat being given her by Mrs. Selig, the only statement she made about the hat at all was when she made the affidavit. We didn’t know anything about the hat before. Nobody threatened her when she was there. When the first questioning was going on Campbell and Starnes were not in there. They came in when we called them and told them we were ready. Her attorney, Mr. Gordon, came in with the detectives.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

As to why we didn’t take her statement when she denied saying all those things, because we didn’t believe them. We were down there about three hours. We went down there to try and get Minola McKnight out, if we could. We asked Mr. Dorsey to get her out. He said he would let us stand her bond, and he referred us to the detectives to make arrangements. As to why we didn’t get her out then, we wanted a statement from her if we could get it. No, I didn’t know that whenever the detectives got the story they wanted, they would let her out. As to my going to get her out and then grilling her for three hours, I didn’t tell her I was going to get her out; I went down there to get her out, but she left there before I did. She went out of the room. The detectives treated her very nice. They let her go after she made the statement. I knew they were holding her because she did not make a statement confirming her husband. It was not my object to make her statement agree with her husband’s statement, but it was my duty as a good citizen to make her tell the truth.

Dr. S.C. Benedict testified that one of the defense medical experts had a grudge against Dr. Harris, the prosecution’s main medical expert. This was followed by several streetcar motormen who stated that the streetcars often arrived ahead of schedule, which tended to minimize the effect of the testimony of the motormen called by the defense, who had claimed that since the streetcar schedule was rigorously adhered to, Mary Phagan must have arrived later than Leo Frank’s original estimate of five to ten minutes after noon. There was a great deal of testimony later regarding the timing of Mary Phagan’s arrival — and the amount of time which had passed since her late breakfast.

Ultimately, no one really doubted that Mary Phagan had arrived at Leo Frank’s office just a few minutes after noon on April 26 — and had met her death a very few minutes after that.

J. H. HENDRICKS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am a motorman for the Georgia Railway & Electric Company. On April 26th I was running a street car on the Marietta line to the Stock Yards on Decatur Street. I couldn’t say what time we got to town on April 26th, about noon. I have no cause to remember that day. The English Avenue car, with Matthews and Hollis has gotten to town prior to April 26th, ahead of time. I couldn’t say how much ahead of time. I have seen them come in two or three minutes ahead of time; that day they came about 12:06. Hollis would usually leave Broad and Marietta Streets on my car. I couldn’t swear positively what time I got to Broad and Marietta Streets on April 26th. I couldn’t swear what time Hollis and Matthews got there that day. I don’t know anything about that. Often they get there ahead of time. Sometimes they are punished for it.

J. C. McEWING, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am a street car motorman. I ran on Marietta and Decatur Street April 26th. My car was due in town at ten minutes after the hour on April 26th. Hollis’ and Matthews ‘ car was due there 7 minutes after the hour. Hendricks car was due there 5 minutes after the hour. The English Avenue frequently cut off the White City car due in town at 12:05. The White City car is due there before the English Avenue. It is due 5 minutes after the hour and the Cooper Street is due 7 minutes after. The English Avenue would have to be ahead of time to cut off the Cooper Street car. That happens quite often. I have come in ahead of time very often. I have known the English Avenue car to be 4 or 5 minutes ahead of time.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I don’t know when that happened or who ran the car. I don’t know whether they ran on schedule time on April 26th, or not. When one car is cut off, one might be ahead of time, and one might be behind time. It’s reasonable to suppose that the five minutes after car ought to come in ahead of the one due seven minutes after. If it was behind it would be cut off, just as easy as the other one would be cut off by being ahead.

M. E. McCOY, sworn for the State, in rebuttal.

I knew Mary Phagan. I saw her on April 26th, in front of Cooledge’s place at 12 Forsyth Street. She was going towards pencil company, south on Forsyth Street on right hand side. It was near twelve o’clock. I left the corner of Walton and Forsyth Street exactly twelve o’clock and came straight on down there. It took me three or four minutes to go there.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I know what time it was because I looked at my watch. First time I told it was a week ago last Saturday, when I told an officer. I didn’t tell it because I didn’t want to have anything to do with it. I didn’t consider it as a matter of importance until I saw the statement of the motorman of the car she came in on, and I knew that was wrong. She was dressed in blue, a low, chunky girl. Her hair was not very dark. She had on a blue hat.

GEORGE KENDLEY, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am with the Georgia Railway & Power Co. I saw Mary Phagan about noon on April 26th. She was going to the pencil factory from Marietta Street. When I saw her she stepped off of the viaduct.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I was on the front end of the Hapeville car when I saw her. It is due in town at 12 o’clock. I don’t know if it was on time that day. I told several people about seeing her the next day. If Mary Phagan left home at 10 minutes to 12, she ought to have got to town about 10 minutes after 12, somewhere in that neighborhood. She could not have gotten in much earlier. The time that I saw her is simply an estimate. That was the time my car was due in town. I remember seeing her by reading of the tragedy the next day. I didn’t testify at the Coroner’s inquest because nobody came to ask me. No, I have not abused and villified Frank since this tragedy. No, I have not made myself a nuisance on the cars by talking of him. I know Mr. Brent. I didn’t tell him that Mr. Frank’s children said he was guilty. Mr. Brent asked me what I thought about it several times on the car. He has always been the aggressor. As to whether I abused and villified him in the presence of Miss Haas and other passengers, there has been so much talk that I don’t know what has been said. I don’t think I said if he was released I would join a party to lynch him. Somebody said if he got out there might be some trouble. I don’t remem- ber saying that I would join a party to help lynch him if he got out. I talked to Mr. Leach about it. I don’t remember what I told him. I told him I saw her over there about 12 o’clock. That was the time the car was due in town. I know I saw her before 12:05. My car was on schedule time. I couldn’t swear it was exactly on the minute.

HENRY HOFFMAN, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am inspector of the street car company. Matthews is under me a certain part of the day. On April 26th he was under me from 11:30 to 12:07. His car was due at Broad and Marietta at 12:07. There is no such schedule as 12:07 and half. I have been on his car when we cut off the Fair Street car. Fair Street car is due at 12:05. I have compared watches with him. They vary from 20 to 40 seconds. We are supposed to carry the right time. I have called Matthews attention to running ahead of schedule once or twice. They come in ahead of time on relief time for supper and dinner.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I don’t know anything about his coming on April 26th. We found out he was ahead of time way along last March. He was a minute and a half ahead. I have caught him as much as three minutes ahead of time last spring, on the trip due in town 12:07. I didn’t report him, I just talked to him. I have known him to be ahead of time twice in five years while he was under my supervision.

N. KELLY, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am a motorman of the Georgia Railway & Power Co. On April 26th, I was standing at the corner of Forsyth and Marietta Street about three minutes after 12. I was going to catch the College Park car home about 12:10. I saw the English Avenue car of Matthews and Mr. Hollis arrive at Forsyth and Marietta about 12:03. I knew Mary Phagan. She was not on that car. She might have gotten off there, but she didn’t come around. I got on that car at Broad and Marietta and went around Hunter Street. She was not on there.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I didn’t say anything about this because I didn’t want to get mixed up in it. I told Mr. Starnes about it this morning. I have never said anything about it before. That car was due in town at 12:07. The Fair Street car was behind it.

W. B. OWENS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I rode on the White City line of the Georgia Railway & Electric Co. It is due at 12:05. Two minutes ahead of the English Avenue car. We got to town on April 26th, at 12:05. I don’t remember seeing the English Avenue car that day. I have known that car to come in a minute ahead of us, sometimes two minutes ahead. That was after April 26th. I don’t recall whether it occurred before April 26th.

LOUIS INGRAM, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am a conductor on the English Avenue line. I came to town on that car on April 26th. I don’t know what time we came to town. I have seen that car come in ahead of time several times, sometimes as much as four minutes ahead. I know Matthews, the motorman. I have ridden in with him when he was ahead of time several times.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

It is against the rules to come in ahead of time, and also to come in behind time. They punish you for either one.

W. M. MATTHEWS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I have talked with this man Dobbs (W. C.) but I don’t know what I talked about. I have never told him or anybody that I saw Mary Phagan get off the car with George Epps at the corner of Marietta and Broad. It has been two years since I have been tried for an offense in this court.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I was acquitted by the jury. I had to kill a man on my car who assaulted me.

W. C. DOBBS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

Motorman Matthews told me two or three days after the murder that Mary Phagan and George Epps got on his car together and left at Marietta and Broad Streets.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

Sergeant Dobbs is my father.

W. W. ROGERS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

On Sunday morning after the murder, I tried to go up the stairs leading from the basement up to the next floor. The door was fastened down. The staircase was very dusty, like it had been some little time since it had been swept. There was a little mound of shavings right where the chute came down on the basement floor. The bin was about a foot and a half from the chute.

SERGEANT L. S. DOBBS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I saw Mr. Rogers on Sunday try to get in that back door leading up from basement in rear of factory. There were cobwebs and dust there. The door was closed.

O. TILLANDER, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

Mr. Graham and I went to the pencil factory on April 26th, about 20 minutes to 12. We went in from the street and looked around and I found a negro coming from a dark alley way, and I asked him for the office and he told me to go to the second floor and turn to the right. I saw Conley this morning. I am not positive that he is the man. He looked to be about the same size. When I went to the office the stenographer was in the outer office. Mr. Frank was in the inner office sitting at his desk. I went there to get my step-son’s money.

E. K. GRAHAM, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I was at the pencil factory April 26th, with Mr. Tillander, about 20 minutes to 12. We met a negro on the ground floor. Mr. Tillander asked him where the office was, and he told him to go up the steps. I don’t know whether it was Jim Conley or not. He was about the same size, but he was a little brighter than Conley. If he was drunk I couldn’t notice it, I wouldn’t have noticed it anyway.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

Mr. Frank and his stenographer were upstairs. He was at his desk. I didn’t see any lady when I came out.

J. W. COLEMAN, sworn for the State in rebuttal. [Mary Phagan’s stepfather. — Ed.]

I remember a conversation I had with detective McWorth. [McWorth was the Pinkerton man, later dismissed, who claimed to have discovered a “bloody club” and part of Mary Phagan’s pay envelope on the first floor, long after other detectives had thoroughly searched the area. –Ed.] He exhibited an envelope to me with a figure “5” on the right of it.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

This does not seem to be the envelope he showed me. (Defendant’s Exhibit 47). The figure “5” was on it. I don’t see it now. I told him at the time that Mary was due $1.20, and that “5” on the right would not suit for that.

J. M. GANTT, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I have seen Leo Frank make up the financial sheet. It would take him an hour and a half after I gave him the data. [This in contrast to the repeated claim by Frank that he needed all afternoon. — Ed.]

IVY JONES (c[olered]), sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I saw Jim Conley at the corner of Hunter and Forsyth Streets on April 26th. He came in the saloon while I was there, between one and two o’clock. He was not drunk when I saw him. The saloon is on the opposite corner from the factory. We went on towards Conley’s home. I left him at the corner of Hunter and Davis Street a little after two o’clock.

HARRY SCOTT, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I picked up cord in the basement when I went through there with Mr. Frank. Lee’s shirt had no color on it, excepting that of blood. I got the information as to Conley’s being able to write from McWorth when I returned to Atlanta. As to the conversation Black and I had, with Mr. Frank about Darley, Mr. Frank said Darley was the soul of honor and that we had the wrong man; that there was no use in inquiring about Darley and he knew Darley could not be responsible for such an act. I told him that we had good information to the effect that Darley had been associating with other girls in the factory; that he was a married man and had a family. Mr. Frank didn’t seem to know anything about that. He said it was a peculiar thing for a man in Mr. Darley’s position to be associating with factory employees, if he was doing it.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

We left after about two hours interview.

L. T. KENDRICK, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I was night watchman at the pencil factory for something like two years. I punched the clocks for a whole night’s work in two or three minutes. The clock at the factory needed setting about every 24 hours. It varied from three to five minutes. That is the clock slip I punched (State’s Exhibit P). I don’t think you could have heard the elevator on the top floor if the machinery was running or anyone was knocking on any of the floors. The back stairway was very dusty and showed that they had not been used lately after the murder. I have seen Jim Conley at the factory Saturday afternoons when I went there to get my money.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I generally got to the factory about a quarter of two to two-thirty. The clock was usually corrected every morning. The clock would run slow sometimes and sometimes fast.

VERA EPPS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

My brother George was in the house when Mr. Minar was asking us about the last time we saw Mary Phagan. I don’t know if he heard the questions asked. George didn’t tell him that he didn’t see Mary that Saturday. I told him I had seen Mary Phagan Thursday.

C. J. MAYNARD, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I have seen Brutus Dalton go in the factory with a woman in June or July, 1912. She weighed about 125 pounds. It was between 1:30 and 2 o’clock in the afternoon on a Saturday.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I was ten feet from the woman. I didn’t notice her very particularly. I did not speak to them.

W. T. HOLLIS, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

Mr. Reed rides out with me every morning. I don’t remember talking to J. D. Reed on Monday, April 29th, and telling him that George Epps and Mary Phagan were on my car together. I didn’t tell that to anybody. I say like I have always said, that if he was on the car I did not see him.

J. D. REED, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

Mr. Hollis told me on Monday, April 28th, that Epps had gotten on the car and taken his seat next to Mary, and that the two talked to each other all the way as though they were little sweethearts.

J. N. STARNES, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

There were no spots around the scuttle hole where the ladder is immediately after the murder. Campbell and I arrested Minola McKnight, to get a statement from her. We turned her over to the patrol wagon and we never saw her any more until the following day, when we called Mr. Craven and Mr. Pickett to come down and interview her. We stayed on the outside while she was on the inside with Craven and Pickett. They called us back and I said to her, “Minola, the truth is all we want, and if this is not the truth, don’t you state it.” And she started to put the statement down. Mr. Gordon, her attorney, was on the outside, and I told him we could go inside without his making any demand on me, and he went in with me, and Mr. Febuary had already taken down part of the statement and I stopped him and made him read over what he had already taken down, and after she had finished the statement, Attorney Gordon went to Mr. Dorsey’s office and then he came back to the police station. After he returned the affidavit was read over in the presence of Mr. Pickett, Craven, Campbell, Albert McKnight and Attorney Gordon and she signed it in our presence. You (Mr. Dorsey) had nothing to do with holding her. You told me over the phone that you couldn’t say what I could do, but that I could do what I pleased about it.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

No, I did not lock her up because she didn’t give us the right kind of statement; as to the authority I had to lock her up, it was reasonable and right that she should be locked up. I did that for the best interest of the case I was working on. No, I didn’t have any warrant for her arrest. She was brought to Mr. Dorsey’s office by a bailiff by a subpoena. I took her away from Dorsey’s office and put her in a patrol wagon. I expect Mr. Dorsey knew we were going to lock her up, but he did not tell us to do it. No, he didn’t disapprove of it. I didn’t know anything about her having made a previous statement to Mr. Dorsey. I think Mr. Dorsey said she had made such a statement. I saw her the next day in the station house. She didn’t scream after leaving Dorsey’s office until she reached the sidewalk. And then she commenced hollering and carrying on that she was going to jail; that she didn’t know anything about it, or something like that. No, I had no warrant for her arrest. She had committed no crime. I held her to get the truth. Mr. Dorsey told me I could turn her loose as I pleased. That was after she made the statement. I told him as to what had occurred and that her attorney, Gordon, was coming up there to see him. I told Col. Gordon that if it was agreeable with Col. Dorsey, that Minola could go as far as we were concerned. Well, Mr. Dorsey had more or less to do with the case that I was working on and I wanted to act on his advice and consent. He called me on the telephone and told me that if the chief thought it best or if we thought it best after conferring, to just let her go.

DR. CLARENCE JOHNSON, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am a specialist on diseases of the stomach and intestines. I am a physiologist. A physiologist makes his searches on the living body; the pathologist makes his on a dead body.

If you give any one who has drunk a chocolate milk at about eight o’clock in the morning, cabbage at 12 o’clock and 30 or 40 minutes thereafter you take the cabbage out and it is shown to be dark like chocolate and milk, that much contents of any kind vomited up three and a half hours afterwards would show an abnormal stomach. It doesn’t show a normal digestion.

If a little girl who eats a dinner of cabbage and bread at 11:30 is found the next morning dead at 3 a. m., with a rope around her neck, indented and the flesh sticking up, bruised on the eye, blood on the back of her head, the tongue sticking out, blue skin, every indication that she came to her death from strangulation, her head down, rigor mortis had been on her twenty hours, the blood had settled in her where the gravity would naturally take it in the face, she is embalmed, formaldehyde is used and injected in the various cavities of the body, including the stomach, a pathologist takes her stomach a week or ten days after, finds cabbage of that size (State’s Ex- hibit G) in the stomach, finds starch granules undigested, and finds in the stomach that the pyloris is still closed, that there is nothing in the first six feet of the small intestines; that there is every indication that digestion had been progressing favorably, and finds thirty-two degrees hydrochloric acid, and if the pathologist is capable and finds that there was only combined hydrochloric acid and that there was no abnormal condition of the stomach, the six feet of the intestines was empty, I would say that the digestion of bread and cabbage was stopped within an hour after they were eaten. That would not be a wild guess in my opinion.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

The bruises on the head, the evidence of strangulation and other injuries about the head are other possible factors which must be taken into consideration. Anything which disturbs the circulation of the blood, or hinders the action of the nerves controlling the stomach, especially the secretion, prevents the development of the characteristics found in normal digestion one hour after a meal. I mean by mechanical condition of the stomach, no change in the size or thickness, or opening into the intestines, or size or thickness of intestines. The test should be made with absolute accuracy with these acids. The color test is generally accepted. A man’s eye has to be absolutely correct to make the color test.

The degree of acidity in a normal stomach varies from 30 to 45 degrees, according to the stomach and what is in it. The formaldehyde would make no change on the physical property on the pancreatic juice found in the small intestine after death. There would be hardly any change on its chemical property. When it comes in contact with the formaldehyde it is supposed to be preserved. It has some neutralizing effect on the alkali present. That decomposes in time after death, unless hindered by some preservative. The hydrochloric acids in the stomach also disappear if the stomach has disintegrated and the preservative has disappeared. It disappears like the other fluids and tissues of the body unless hindered by some preservative agent. Sometimes digestion is delayed a good deal even in a normal stomach by insufficient mastication, too much diluting of the juices, or anything that hinders the operation of the mechanical effect. Insufficient mastication is one of the commonest causes, also the taking of too much liquid. Fatigue occasioned by extensive walking would hinder it. If the walking was not too extensive to produce fatigue, it would help digestion in a normal stomach. Insufficient mastication is the worst cause of delayed digestion. My estimate was that the cabbage was found an hour after the process of digestion had begun. I did not undertake to say when the digestion began. You can’t tell by looking at food in a bottle how much the failure to masticate it delayed digestion in hours and minutes. It would be just an estimate.

The physical appearance of that cabbage (Defendant’s Exhibit 88) shows indigestion by the layer, character and size, and area of separation between, and the character and arrangement of the layers below. The mere fact that it was vomited up would be proof positive that no scientific opinion could be made about it. To make a scientific test I would have to test the mechanism of the stomach, the time it was in there and the degree and presence of the different acids. The chocolate milk would not naturally stay in a normal stomach five or six hours. The cabbage would stay in a normal empty stomach where there was a tomato also three or four hours. I never made any test of Mary Phagan’s stomach and examined the contents of it.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

160 cubic cc. of liquid in the stomach taken out nine days afterwards would be a little in excess of what I would consider normal under the conditions already named.

DR. GEORGE M. NILES, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I confine my work to diseases of digestion. Every healthy stomach has a certain definite and orderly relation to every other healthy stomach. Assuming a young lady between thirteen and fourteen years of age at 11:30 April 26, 1913, eats a meal of cabbage and bread, that the next morning about three o’clock her dead body is found. That there are indentations in her neck where a cord had been around her throat, indicating that she died of strangulation, her nails blue, her face blue, a slight injury on the back of the head, a contused bruise on one of her eyes, the body is found with the face down, rigor mortis had been on from sixteen to twenty hours, that the blood in the body has settled in the part where gravity would naturally carry it, that the body is embalmed immediately with a fluid consisting chiefly of formaldehyde, which is injected in the veins and cavities of the body; that she is disinterred nine days thereafter; that cabbage of this texture (State’s Exhibit G) is found in her stomach; that the position of the stomach is normal; that no inflammation of the stomach is found by microscopic investigation; that no mucous is found, and that the glands found under this microscope are found to be normal, that there is no obstruction to the flow of the contents of the stomach to the small intestine; that the pyloris is closed; that there is every indication that digestion was progressing favorably; that in the gastric juices there is found starch granules that are shown by the color test to have been undigested, and that in that stomach you also find thirty-two degrees of hydrochloric acid, no maltose, no dextrin, no free hydrochloric acid (there would be more or less free hydrochloric acid in the course of an hour or more in the orderly progress of digestion of a healthy stomach where the contents are carbohydrates), I would say that indicated that digestion had been progressing less than an hour.

The starch digestion should have progressed beyond the state erythrodextrin in course of an hour. There should have been enough free acid to have stimulated the pyloris to relax to a certain extent, and there should have been some contents in the duodenum. I am assuming, of course, that it is a healthy stomach and that the digestion was not disturbed by any psychic cause which would disturb the mind or any severe physical exercise. I am not going so much on the physical appearance of the cabbage. Any severe physical exercise or mental stress has quite an influence on digestion. Death does not change the composition of the gastric juices when combined with hydrochloric acid for quite awhile. The gastric juices combined with the hydrochloric acid are an antiseptic or preservative. There is a wide variation in diseased stomachs as to digestion.

CROSS EXAMINATION

There are idiosyncracies in a normal stomach, but where they are too marked I would not consider that a normal stomach. I wouldn’t say that there is a mechanical rule where you can measure the digestive power of every stomach for every kind of food. There is a set time for every stomach to digest every kind of food within fairly regular limits, that is, a healthy stomach. There is a fairly mixed standard. There is no great amount of variation between healthy stomachs. I can’t answer for how long it takes cabbage to digest. I have taken cabbage out of a cancerous stomach that had been in there twenty-four hours, but there was no obstruction. The longest time that I have taken cabbage out of a fairly normal stomach was between four and five hours. That was where it was in the stomach along with another meal. I found the cabbage among the remains of the meal four or five hours after it had been eaten.

Mastication is a very important function of digestion. Failure to masticate delays the starch digestion. Starch and cabbage are both carbohydrates. I would say that if cabbage went into a healthy stomach not well masticated, the starch digestion would not get on so well, but the stomach would get busy at once. Of course, it would not be prepared as well. The digestion would be delayed, of course. That cabbage is not as well digested as it should have been (State’s exhibit G), but the very fact of your anticipating a good meal, smelling it, starts your saliva going and forms the first stage of digestion, and digestion is begun right there in the mouth, even if you haven’t chewed it a single time. Any deviation from good mastication retards digestion.

I couldn’t presume to say how long that cabbage lay in Mary Phagan’s stomach. I believe if it had been a live, healthy stomach and the process of digestion was going on orderly, it would be pulverized in four or five hours. It would be more broken up and tricturated than it is. I wouldn’t consider that a wild guess. I think it would have been fairly well pulverized in three hours. Chewing amounts to a great deal, but there should be an amount of saliva in her stomach even if she hadn’t masticated it thoroughly. Chewing is a temperamental matter to a great extent. One man chews his meal quicker than another. If it isn’t chewed at all, the stomach gets busy and helps out all it can and digests it after awhile. It takes more effort, of course, but not necessarily more time. What the teeth fail to do the stomach does to a great extent. The stomach has an extra amount of work if it is not masticated. You can’t tell by looking at the cabbage how long it had been undergoing the process of digestion. If that was a healthy stomach with combined acid of 32 degrees, and nothing happened either physical or mental to interfere with digestion, those laboratory findings indicated that digestion had been progressing less than an hour. I never made an autopsy or examination of the contents of Mary Phagan’s stomach.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

The first stage of digestion is starch digestion. This progresses in the stomach until the contents become acid in all its parts. Then the starch digestion stops until the contents get out in the intestines and become alkaline in reaction; then the starch digestion is continued on beyond. The olfactories act as a stimulant to the salivary glands.

DR. JOHN FUNK, sworn for the State in rebuttal.

I am professor of pathology and bacteriologist. I was shown by Dr. Harris sections from the vaginal wall of Mary Phagan, sections taken near the skin surface. I didn’t see sections from the stomach or the contents. These sections showed that the epithelium wall was torn off at points immediately beneath that covering in the tissues below, and there was infiltrated pressure of blood. They were, you might say, engorged, and the white blood cells in those blood vessels were more numerous than you will find in a normal blood vessel. The blood vessels at some distance from the torn point were not so engorged to the same extent as those blood vessels immediately in the vicinity of the hemorrhage. Those blood vessels were larger than they should be under normal circumstances, as compared with the blood vessels in the vicinity of the tear. You couldn’t tell about any discoloration, but there was blood there. It is reasonable to suppose that there was swelling there because of the infiltrated pressure of the blood in the tissues. Those conditions must have been produced prior to death, because the blood could not invade the tissues after death.

If a young lady, between thirteen and fourteen years old eats at eleven thirty a. m. a normal meal of bread and cabbage on a Saturday and at three a. m. Sunday morning she is found with a cord around her neck, the skin indented, the nails and flesh cyanotic, the tongue out and swollen, blue nails, everything indicating that she had been strangled to death, that rigor mortis had set in, and according to the best authorities had probably progressed from sixteen to twenty hours, and she was laying face down when found, and gravity had forced the blood into that part of the body next to the ground, that it had discolored her features, that immediately thereafter, between ten and two o’clock she was embalmed with a fluid containing usual amount of formaldehyde, this being injected into the veins in the large cavities, she is interred thereafter and in about a week or ten days she is disinterred, and you find in her stomach cabbage like that (State’s Exhibit G) and you find granules of starch undigested, and those starch granules are developed by the usual color tests, and you also find in that stomach thirty-two degrees of combined hydrochloric acid, the pyloris closed, and the duodenum, and six feet of the small intestines empty, no free hydrochloric acid being present at all, nor dextrin, or erythrodextrin being found in any degree, and the uterus was somewhat enlarged, and the walls of the vagina show dilation and swelling, I would say that under those conditions that the epithelium was torn off before death, because of the changes in the blood vessels and tissues below the epithelium covering, and because of the presence of blood.

I would not express an opinion as to how long cabbage had been in the stomach, from the appearance of the cabbage itself, taking into consideration the combined hydrochloric acid of thirty-two degrees, the emptiness of the small intestine, the presence of starch granules, and the absence of free hydrochloric acid, one can’t say positively, but it is reasonable to assume that the digestion had pro- gressed probably an hour, maybe a little more, maybe a little less.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

Dr. Dorsey asked me to examine the sections of the vaginal wall last Saturday. The sections I examined were about a quarter of an inch wide and three-quarters of an inch long. It was about nine twenty-five thousandths of an inch thick, that is, much thinner than tissue paper. I examined thirty or forty little strips. That was after this trial began. I was not present at the autopsy. As soon as a tissue receives an injury, it reacts in a very short time. The reaction shows up in the changes of the blood vessels. You can tell by the appearance of the blood vessels whether the injury was before death or not, and you can give an approximate idea as to the length of time before death. I do not know from what body the sections were taken. I know that it was from a human vagina.

THE STATE CLOSES.

EVIDENCE FOR DEFENDANT IN SUR-REBUTTAL.

T. Y. BRENT, sworn for the Defendant in sur-rebuttal.

I have heard George Kendley on several occasions express himself very bitterly towards Leo Frank. He said he felt in this case just as he did about a couple of negroes hung down in Decatur; that he didn’t know whether they had been guilty or not, but somebody had to be hung for killing those street car men and it was just as good to hang one nigger as another, and that Frank was nothing but an old Jew and they ought to take him out and hang him anyhow.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I have been employed by the defense to assist in subpoenaing witnesses. I took the part of Jim Conley in the experiment conducted by Dr. Win. Owens at the factory on Sunday.

M. E. STAHL, sworn for the Defendant, in sur-rebuttal.

I have heard George Kendley, the conductor, express his feelings toward Leo Frank. I was standing on the rear platform, and he said that Frank was as guilty as a snake, and should be hung, and that if the court didn’t convict him that he would be one of five or seven that would get him.

MISS C. S. HAAS, sworn for the Defendant, in sur-rebuttal.

I heard Kendley two weeks ago talk about the Frank case so loud that the entire street car heard it. He said that circumstantial evidence was the best kind of evidence to convict a man on and if there was any doubt, the State should be given the benefit of it, and that 90 per cent. of the best people in the city, including himself, thought that Frank was guilty and ought to hang.

N. SINKOVITZ, sworn for the Defendant, in sur-rebuttal.

I am a pawnbroker. I know M.E. McCoy. He has pawned his watch to me lately. The last time was January 11, 1913. It was in my place of business on the 26th of April, 1913. He paid up his loan on August 16th, last Saturday, during this trial. This is the same watch I have been handling for him during the last two years.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

My records here show that he took it out Saturday.

S. L. ASHER, sworn for the Defendant in sur-rebuttal.

About two weeks ago I was coming to town between 5 and 10 minutes to 1 on the car and there was a man who was talking very loud about the Frank case, and all of a sudden he said: “They ought to take that damn Jew out and hang him anyway.” I took his number down to report him.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I have not had a chance to report since it happened.

It is most interesting that a single man, expressing his opinion that Leo Frank was a “damn Jew” and ought to hang, was something that a public-spirited citizen in 1913 Atlanta thought he ought to report to the authorities. This hardly corresponds with the atmosphere of “pervasive Southern anti-Semitism” that modern Frank supporters say existed. On the contrary, it speaks of an atmosphere in which such sentiments were strongly deplored, and even considered beyond the pale of socially acceptable behavior and expression.

During the final moments of the trial itself, and before closing arguments were made, Leo Max Frank asked to address the court once again. He was permitted to do so. As before, he was unsworn and not under oath and not subject to cross-examination, just as in his initial statement. No matter what Frank told the jury, Dorsey was forbidden to question him about it, or make it the basis for questioning anyone else.

ADDITIONAL STATEMENT MADE BY DEFENDANT, LEO M. FRANK.

In reply to the statement of the boy that he saw me talking to Mary Phagan when she backed away from me, that is absolutely false, that never occurred. In reply to the two girls, Robinson and Hewel, that they saw me talking to Mary Phagan and that I called her” Mary,” I wish to say that they are mistaken. It is very possible that I have talked to the little girl in going through the factory and examining the work, but I never knew her name, either to call her “Mary Phagan,” “Miss Phagan,” or “Mary.”

In reference to the statements of the two women who say that they saw me going into the dressing room with Miss Rebecca Carson, I wish to state that that is utterly false. It is a slander on the young lady, and I wish to state that as far as my knowledge of Miss Rebecca Carson goes, she is a lady of unblemished character.

DEFENDANT CLOSES.

So to the very end, Leo Frank maintained that all the witnesses who heard him calling Mary Phagan by name were liars — or mistaken. Interestingly, he did not take even a moment at the end of the trial to repeat his claim that he never made lascivious advances toward the young ladies under his supervision — as several of them had so recently testified. Most likely he was warned off the topic by his counsel.

In our next article, we will present the powerful, yet completely contradictory, closing arguments of both the prosecution and defense in the trial of Leo M. Frank.