AT THE CLIMAX of the Leo Frank trial, an admission was made by the defendant that amounted to a confession during trial. How many times in the annals of US legal history has this happened? Something very unusual happened during the month-long People v. Leo M. Frank murder trial, held within Georgia’s Fulton County Superior Courthouse in the Summer of 1913. I’m going to show you evidence that Mr. Leo Max Frank inadvertently revealed the solution to the Mary Phagan murder mystery.

In addition to being an executive of Atlanta’s National Pencil Company, Leo Frank was also a B’nai B’rith official — president of the 500-member Gate City Lodge in 1912 — and even after his conviction and incarceration Frank was elected lodge president again in 1913. As a direct result of the Leo Frank conviction, the B’nai B’rith founded their well-known and politically powerful “Anti-Defamation League,” or ADL.

When Leo Frank mounted the witness stand on Monday afternoon, August 18, 1913, at 2:15 pm, he orally delivered an unsworn, four-hour, pre-written statement to the 250 people present.

Epic Trial of 20th Century Southern History

The audience sat in the grandstand seats of the most spectacular murder trial in the annals of Georgia history. Nestled deep within the pews of the Fulton County Superior Court were the luckiest of public spectators, defense and prosecution witnesses, journalists, officials, and courtroom staff.

Like gladiators in an arena, in the center of it all, with their backs to the audience, seated in ladder-back chairs, were the most important principals. They were the State of Georgia’s prosecution team, made up of three members, led by Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey and Frank Arthur Hooper. Arrayed against them were eight Leo Frank defense counselors, led by Luther Z. Rosser and Reuben Rose Arnold. The presiding judge, the Honorable Leonard Strickland Roan, sitting in a high-backed leather chair, was separated by the witness stand from the jury of 12 white men who were sworn to justly decide the fate of Leo Frank.

Crouched and sandwiched between the judge’s bench and the witness chair, sitting on the lip of the bench’s foot rail, was a stenographer capturing the examinations. Stenographers clicked away throughout the trial and were changed regularly in relays.

Surrounding the four major defense and prosecution counselors were an entourage of uniformed police, plainclothes detectives, undercover armed security men, government staff, and magistrates.

The first day of the Leo Frank trial began on Monday morning, July 28, 1913, and led to many days of successively more horrifying revelations. But the most interesting day of the trial occurred three weeks later when Leo Frank sat down in the witness stand on Monday afternoon, August 18, 1913.

The Moment Everyone Was Waiting For

What Leo Frank had to say to the court became the spine-tingling climax of the most notorious criminal trial in US history, and it was the moment everyone in all of Georgia, especially Atlanta, had waited for.

Judge Roan explained to the jury the unique circumstances and rules concerning the unsworn statement Leo M. Frank was to make. Then, at 2:14 pm, Leo Frank was called to speak. When he mounted the stand, a hush fell as 250 spellbound people closed ranks and leaned forward expectantly. They were more than just speechless: They were literally breathless, transfixed, sitting on the edges of their seats, waiting with great anticipation for every sentence, every word, that came forth from the mouth of Leo Frank.

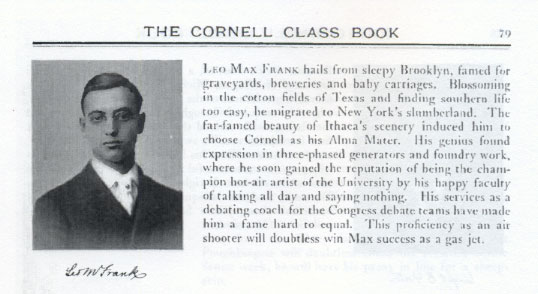

But listening to his long speech became challenging at times. He had a reputation as a “gas jet” from his college days (see his college yearbook entry), and he lived up to it now with dense, mind-numbing verbiage.

Three Out of Nearly Four Hours: Distractions and Endless Pencil Calculations

To bring his major points home during his almost four-hour speech, Leo Frank presented original pages of his accounting books to the jury. For three hours he went over, in detail, the accounting computations he had made on the afternoon of April 26, 1913. This was meant to show the court that he had been far too busy to have murdered Mary Phagan on that day nearly 15 weeks before.

One point emphasized by the defense was how long it took Frank to do the accounting books: Was it an hour and a half as some said, or three hours? Can either answer ever be definitive, though? No matter how quickly one accountant works, is it beyond belief that another could be twice as fast?

The Ultimate Question Waiting to be Answered

The most important unanswered question in the minds of everyone at the trial was this: Where had Leo Frank gone between 12:05 pm and 12:10 pm on Saturday, April 26, 1913? This was the crucial question because Monteen Stover had testified she found Leo Frank’s office empty during this five-minute time segment – and Leo Frank had told police he never left his office during that time. And the evidence had already shown that Mary Phagan was murdered sometime between 12:05 and 12:15 pm in the Metal Room of the same factory where Leo Frank was present.

There weren’t a plethora of suspects in the building: April 26, 1913, was a state holiday in Georgia — Confederate Memorial Day — and the factory and offices were closed down, except for a few employees coming in to collect their pay and two men doing construction work on an upper floor.

Two investigators had testified that Leo Frank gave them the alibi that he had never left his office from noon until after 12:45. If Leo Frank’s alibi held up, then he couldn’t have killed Mary Phagan.

Everyone wanted to know how Leo Frank would respond to the contradictory testimony clashing with his alibi. And, after rambling about near-irrelevancies for hours, he did: Frank stated — in complete contradiction to his numerous earlier statements that he’d never left his office — that he might have “unconsciously” gone to the bathroom during that time — placing him in the only bathroom on that floor of the building, the Metal Room bathroom. The Metal Room is where Jim Conley stated he had first found the lifeless body of little Mary Phagan, where Mary Phagan’s blood was found, and where the prosecution had spent weeks proving that the murder had actually taken place.

This was doubly amazing because weeks earlier Leo Frank had emphatically told the seven-man panel led by Coroner Paul Donehoo at the Coroners Inquest, that he (Leo Frank) did not use the bathroom all day long — not that he (Leo Frank) had forgotten, but that he had not gone to the bathroom at all. The visually-blind but prodigious savant Coroner Paul Donehoo — with his highly-refined “B.S. detector” was incredulous as might be expected. Who doesn’t use the bathroom all day long? It was as if Leo Frank was mentally and physically, albeit crudely and unbelievably, trying to distance himself from the bathroom where Jim Conley said he found the body.

Furthermore, Leo Frank had told detective Harry Scott — witnessed by a police officer named Black — that he (Leo Frank) was in his office every minute from noon to half past noon, and in State’s Exhibit B (Frank’s stenographed statement to the police), Leo Frank never mentions a bathroom visit all day.

And now he had reversed himself!

Why would Leo Max Frank make such a startling admission, after spending months trying to distance himself from that part of the building at that precise time? That is a difficult question to answer, but there are clues. 1) The testimony of Monteen Stover (who liked Frank and who was actually a supportive character witness for him) that Frank was missing from his office for those crucial five minutes was convincing. Few could believe that Stover — looking to pick up her paycheck, and waiting five minutes in the office for an opportunity to do so — would have been satisfied with a cursory glance at the room and therefore somehow missed Frank behind the open safe door as he had alleged. 2) The evidence suggests that Frank did not always make rational decisions when under stress: Under questioning from investigators, he repeatedly changed the time at which Mary Phagan supposedly came to see him in his office (and State’s Exhibit B shows that Frank, in the presence of his lawyers, told police that Mary Phagan was in his office with him alone between 12:05 and 12:10 pm); he reportedly confessed his guilt to his wife the day of the murder; he, if guilty, reacted out of all proportion and reason to being spurned by his teenage employee; and he maintained the utterly unbelievable position throughout the case that he did not know Mary Phagan by name, despite indisputably knowing her initials (he wrote them on the company books by hand some 52 times!) and interacting with her countless times.

Frank had also said (to paraphrase his statement) that to the best of his recollection when he was in his second floor office from 12:00 to 12:45 pm, and that aside from temporary visitors, the only other people continuously in the building he was aware of were Mr. White and Mr. Denham on the fourth floor, banging away and doing construction as they tore down a partition. That’s it, three people. One can understand investigators, after hearing Frank’s statement that there were only three people in the building, asking the question: If there are three people in the factory, and two of them didn’t do it, who is left?

Even if only one of these lapses is true as described, it is enough to show a pronounced lack of judgement on Frank’s part. A man with such impaired judgement may actually have been unable to see that by explaining away his previous untenable (and now exposed as false) position of “never leaving the office” with an “unconscious” bathroom visit, he was placing himself at the scene of the murder at the precise time of the murder.

Thus are men who tell tales undone, even as they fall back upon a partial truth.

Georgia: Right to Refuse Oaths and Examination

Under the Georgia Code, Section 1036, the accused has the right to make an unsworn statement and, furthermore, to refuse to be examined or cross-examined at his trial. Leo Frank made the decision to make an unsworn statement and not allow examination or cross examination.

The law also did not permit Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey or his legal team to orally interpret or comment on the fact that Leo Frank was not making a statement sworn under oath at his own murder trial. The prosecution respected this rule.

The jury knew that Leo Frank had had months to carefully prepare his statement. But what was perhaps most damaging to Leo Frank’s credibility was the fact that every witness at the trial, regardless of whether they were testifying for the defense or prosecution, had been sworn, and therefore spoke under oath, and had been subject to cross-examination by the other side — except for Leo Frank.

Thus it didn’t matter if the law prevented the prosecution from commenting on the fact Leo Frank had refused cross examination, opting instead to make an unsworn statement, because the jury could see that anyway. Making an unsworn statement and refusing to be examined does not prove that one is guilty, but it certainly raises eyebrows of doubt.

The South an “Honor Bound” Society

Could a sworn jury upholding its sacred duty question Leo Frank’s honor and integrity as a result of what Southerners likely perceived as his cowardly decision under Georgia Code, Section 1036? If so, greater weight would naturally be given to those witnesses who were sworn under oath and who contradicted Leo Frank’s unsworn alibis, allegations, and claims. It put the case under a new lens of the sworn versus the unsworn.

The average Southerner in 1913 was naturally asking the question: What white man would make an unsworn statement and not allow himself to be cross-examined at his own murder trial if he were truly innocent? Especially in light of the fact that the South was culturally white separatist — and two of the major material witnesses who spoke against Leo Frank were African-Americans, one claiming to be an accomplice after the fact turned accuser. In the Atlanta of 1913, African-Americans were perceived as second class citizens and less reliable than whites in terms of their capacity for telling the truth.

Today, we might ask: Why wouldn’t Leo Frank allow himself to be cross examined when he was trained in the art and science of debating during his high school senior year and all through his years in college, where he earned the rank of Cornell Congress Debate Team coach? (Pratt Institute Monthly, June, 1902; Cornellian, 1902 through 1906; Cornell Senior Class Book, 1906; Cornell University Alumni Dossier File on Leo Frank, retrieved 2012)

Odd Discrepancies

Most Leo Frank partisan authors omit significant parts of the trial testimony of Newt Lee and Jim Conley from their retelling of the Leo Frank Case. Both of these black men, former National Pencil Company employees, made clearly damaging statements against Frank.

The evidence Newt Lee brought forward was circumstantial, but intriguing — and never quite adequately explained by Leo Frank then, or by his defenders now.

He stated that on Friday Evening, April 25, 1913, Frank made a request to him, Lee, that he report to work an hour early at 4:00 pm on Confederate Memorial Day, the next day. The stated reason was that Leo Frank had made a baseball game appointment with his brother-in-law, Mr. Ursenbach, a Gentile who was married to one of Frank’s wife Lucille’s older sisters. Leo Frank would eventually give two different reasons at different times as to why he canceled that appointment: 1) he had too much work to do, and 2) he was afraid of catching a cold.

Newt Lee’s normal expected time at the National Pencil Company factory on Saturdays was 5:00 pm sharp. Lee stated that when he arrived an hour early that fateful Saturday, Leo Frank had forgotten the change because he was in an excited state. Frank, he said, was unlike his normal calm, cool and collected “boss-man” self. Normally, if anything was out of order, Frank would command him, saying “Newt, step in here a minute” or the like. Instead, Frank burst out of his office, bustling frenetically towards Lee, who had arrived at the second floor lobby at 3:56 pm. Upon greeting each other, Frank requested that Lee go out on the town and “have a good time” for two hours and come back at 6:00 pm.

Because Leo Frank asked Newt Lee to come to work one hour early, Lee had lost that last nourishing hour of sleep one needs before waking up fully rejuvenated, so Lee requested of Frank that he allow him to take a nap in the Packing Room (adjacent to Leo Frank’s front office). But Frank re-asserted that Lee needed to go out and have a good time. Finally, Newt Lee acquiesced and left for two hours.

At trial, Frank would state that he sent Newt Lee out for two hours because he had work to do. When Lee came back, the double doors halfway up the staircase were locked – very unusual, as they had never had been locked before on Saturday afternoons. When Newt Lee unlocked the doors and went into Leo Frank’s office he witnessed his boss bungling and nearly fumbling the time sheet when trying to put a new one in the punch clock for the night watchman – Lee – to register.

It came out before the trial that Newt Lee had earlier been told by Leo Frank that it was a National Pencil Company policy that once the night watchman arrived at the factory – as Lee had the day of the murder at 4:00 pm – he was not permitted to leave the building under any circumstances until he handed over the reigns of security to the day watchman. Company security necessitated being cautious – poverty, and therefore theft, was rife in the South; there were fire risk hazards; and the critical factory machinery was worth a small fortune. Security was a matter of survival.

The two hour timetable rescheduling – the canceled ball game – the inexplicable sudden security rule waiver – the bumbling with a new time sheet – the locked double doors – and Frank’s suspiciously excited behavior: All were highlighted as suspicious by the prosecution, especially in light of the fact that the “murder notes” – found next to Mary Phagan’s head – physically described Newt Lee, even calling him “the night witch.” And, the prosecutor asked, why did Leo Frank later telephone Newt Lee, not once but two or more times, that evening at the factory?

A “Racist” Subplot?

The substance of what happened between Newt Lee (and janitor James “Jim” Conley – see below) and Leo Frank from April 26, 1913 onward is most often downplayed, censored, or distorted by partisans of Leo Frank.

From the testimony of these two African-American witnesses, we learn of an almost diabolic intrigue calculated to entrap the innocent night watchman Newt Lee. It would have been easy to convict a black man in the white separatist South of that time, where the ultimate crime was a black man having interracial sex with a white woman — to say nothing of committing battery, rape, strangulation, and mutilation upon her in a scenario right out of Psychopathia Sexualis.

The plot was exquisitely formulated for its intended audience, the twelve white men who would decide Leo Frank’s fate. It created two layers of African-Americans between Frank and the murder of Mary Phagan. It wouldn’t take the police long to realize Newt Lee didn’t commit the murder, and, since the death notes were written in dialect, it would leave the police hunting for another black murderer. As long as Jim Conley kept his mouth shut, he wouldn’t hang. So the whole plot rested on Jim Conley – and it took the police three weeks to crack him.

The ugly racial element of this defense ploy is rarely mentioned today. The fact that it was Leo Frank, a Jew (and considered white in the racial separatist Old South), who first tried to pin the rape and murder of Mary Phagan on the elderly, balding, and married African-American Newt Lee (who had no criminal record to boot) is not something that Frank partisans want to highlight. The Leo Frank cheering section also downplays the racial considerations that made Frank, when his first racially-tinged defense move failed and was abandoned, change course for the last time and formulate a new subplot to pin the crime on Jim Conley, the “accomplice after the fact.”

If events had played out as intended, there would have likely been one or two dead black men in the wake of the defense team’s intrigue.

Jim Conley knew too much. He admitted he had helped the real murderer, Leo Frank, clean up after the fact. To prevent Conley, through extreme fear, from revealing any more about the real solution to the crime, and to discredit him no matter what he did, a new theory was needed. Jim Conley certainly was scared beyond comprehension, knowing what white society did to black men who beat, raped, and strangled white girls.

The Accuser Becomes the Accused

The new murder theory posited by the Leo Frank defense was that Jim Conley assaulted Mary Phagan as she walked down the stairs from Leo Frank’s office. Once Phagan descended to the first floor lobby, they said, she was robbed, then thrown down 14 feet to the basement through the two-foot by two-foot scuttle hole at the side of the elevator. Conley then supposedly went through the scuttle hole himself, climbing down the ladder, dragged the unconscious Mary Phagan to the garbage dumping ground in front of the cellar incinerator (known as the “furnace”), where he then raped and strangled her.

But this grotesque racially-tinged framing was to fail in the end — in part because because physicians noticed that the scratch marks on Mary Phagan’s face — she had been dragged face down in the basement — did not bleed, strongly suggesting she was already quite dead when the dragging took place.

Investigators arranged for a conversation to take place between Leo Frank and Newt Lee, who were intentionally put alone together in a police interrogation room at the Atlanta Police Station. The experiment was to see how Frank would interact with Lee and determine if any new information could be obtained.

Once they thought they were alone, Leo Frank scolded Newt Lee for trying to talk about the murder of Mary Phagan, and said that if Lee kept up that kind of talk, they both would go straight to hell.

Star Witnesses

The Jewish community has crystallized around the notion that Jim Conley was the star witness at the trial, and not 14-year-old Monteen Stover who defended Leo Frank’s character — and then inadvertently broke his alibi.

Leo Frank partisans downplay the significance of Monteen Stover’s trial testimony and Leo Frank’s attempted rebuttal of her testimony on August 18, 1913. Governor John M. Slaton also ignored the Stover-Frank incident in his 29-page commutation order of June 21, 1915.

Many Frank partisans have chosen to obscure the significance of Monteen Stover by putting all the focus on Jim Conley, and then claiming that without Jim Conley there would have been no conviction of Leo Frank.

Could they be right? Or could Leo Frank have been convicted on the testimony of Monteen Stover, without the testimony of Jim Conley?

It is a question left for speculation only, because no one ever anticipated the significance of Jim Conley telling the jury that he had found Mary Phagan dead in the Metal Room.

It was not until Leo Frank gave his response to Monteen Stover’s testimony – his explanation of why his second floor business office was empty on April 26, 1913 between 12:05 pm and 12:10 pm – that everything came together tight and narrow.

Tom Watson resolved the “no conviction without Conley” controversy in the September 1915 number of his Watson’s Magazine, but perhaps it is time for a 21st century explanation to make it clear why even the Georgia Supreme Court ruled that the evidence and testimony of the trial sustained Frank’s conviction.

August 18, 1913: You Are the Jury

The four-hour-long unsworn statement of Leo Frank was the crescendo of the trial. (Later, just before closing arguments, Frank himself was allowed the last word. He spoke once more on his own behalf, unsworn this time also, for five minutes, denying the testimony of others that he had known Mary Phagan by name and that he had gone into the dressing room for presumably immoral purposes with one of the company’s other employees.)

Frank would also reaffirm his “unconscious visit” admission in a newspaper interview published by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on March 9th, 1914.

A Poignant Excerpt from Frank Hooper’s Final Arguments:

There was Mary. Then, there was another little girl, Monteen Stover. He never knew Monteen was there, and he said he stayed in his office from 12 until after 1 — never left. Monteen waited around for five minutes. Then she left. The result? There comes for the first time from the lips of Frank, the defendant, the admission that he might have gone to some other part of the building during this time — he didn’t remember clearly…

I will be fair ‘with Frank. When he followed the child back into the metal room, he didn’t know that it would necessitate force to accomplish his purpose. I don’t believe he originally had murder in his heart. There was a scream. Jim Conley heard it. Just for the sake of knowing how harrowing it was, I wish you jurymen could hear a similar scream. It was poorly described by the negro. He said it sounded as if a laugh was broken off into a shriek. He heard it break through the stillness of the hushed building.