Proving That Anti-Semitism Had Nothing to Do With His Conviction — and Proving That His Defenders Have Used Frauds and Hoaxes for 100 Years

by Bradford L. Huie

originally published at The American Mercury

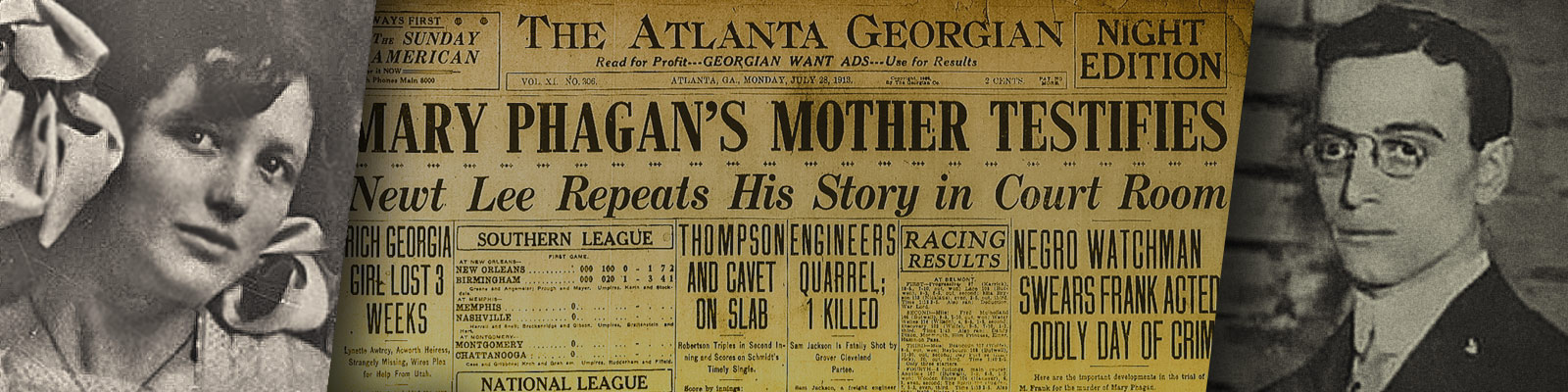

MARY PHAGAN was just thirteen years old. She was a sweatshop laborer for Atlanta, Georgia’s National Pencil Company. A little over 100 years ago — Saturday, April 26, 1913 — little Mary was looking forward to the festivities of Confederate Memorial Day. She dressed gaily and planned to attend the parade. She had just come to collect her $1.20 pay from National Pencil Company superintendent Leo M. Frank at his office when she was attacked by an assailant who struck her down, ripped her undergarments, likely attempted to sexually abuse her, and then strangled her to death. Her body was dumped in the factory basement.

Leo Frank, who was the head of Atlanta’s B’nai B’rith, a Jewish fraternal order, was eventually convicted of the murder and sentenced to hang. After a concerted and lavishly financed campaign by the American Jewish community, Frank’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison by an outgoing governor. But he was snatched from his prison cell and hung by a lynching party consisting, in large part, of leading citizens outraged by the commutation order — and none of the lynchers were ever prosecuted or even indicted for their crime. One result of Frank’s trial and death was the founding of the still-powerful Anti-Defamation League.

Today Leo Frank’s innocence, and his status as a victim of anti-Semitism, are almost taken for granted. But are these current attitudes based on the facts of the case, or are they based on a propaganda campaign that began 100 years ago? Let’s look at the facts.

It has been proved beyond any shadow of doubt that either Leo Frank or National Pencil Company sweeper Jim Conley was the killer of Mary Phagan. Every other person who was in the building at the time has been fully accounted for. Those who believe Frank to be innocent say, without exception, that Jim Conley must have been the killer.

On the 100th anniversary of the inexpressibly tragic death of this sweet and lovely girl, let us examine 100 reasons why the jury that tried him believed (and why we ought to believe, once we see the evidence) that Leo Max Frank strangled Mary Phagan to death — 100 reasons proving that Frank’s supporters have used multiple frauds and hoaxes and have tampered with the evidence on a massive scale — 100 reasons proving that the main idea that Frank’s modern defenders put forth, that Leo Frank was a victim of anti-Semitism, is the greatest hoax of all.

1. Only Leo Frank had the opportunity to be alone with Mary Phagan, and he admits he was alone with her in his office when she came to get her pay — and in fact he was completely alone with her on the second floor. Had Jim Conley been the killer, he would have had to attack her practically right at the entrance to the building where he sat almost all day, where people were constantly coming and going and where several witnesses noticed Conley, with no assurance of even a moment of privacy.

2. Leo Frank had told Newt Lee, the pencil factory’s night watchman, to come earlier than usual, at 4 PM, on the day of the murder. But Frank was extremely nervous when Lee arrived (the killing of Mary Phagan had occurred between three and four hours before and her body was still in the building) and insisted that Lee leave and come back in two hours.

3. When Lee then suggested he could sleep for a couple of hours on the premises — and there was a cot in the basement near the place where Lee would ultimately find the body — Frank refused to let him. Lee could also have slept in the packing room adjacent to Leo Frank’s office. But Frank insisted that Lee had to leave and “have a good time” instead. This violated the corporate rule that once the night watchman entered the building, he could not leave until he handed over the keys to the day watchman. Newt Lee, though strongly suspected at first, was manifestly innocent and had no reason to lie, and had had good relations with Frank and no motive to hurt him.

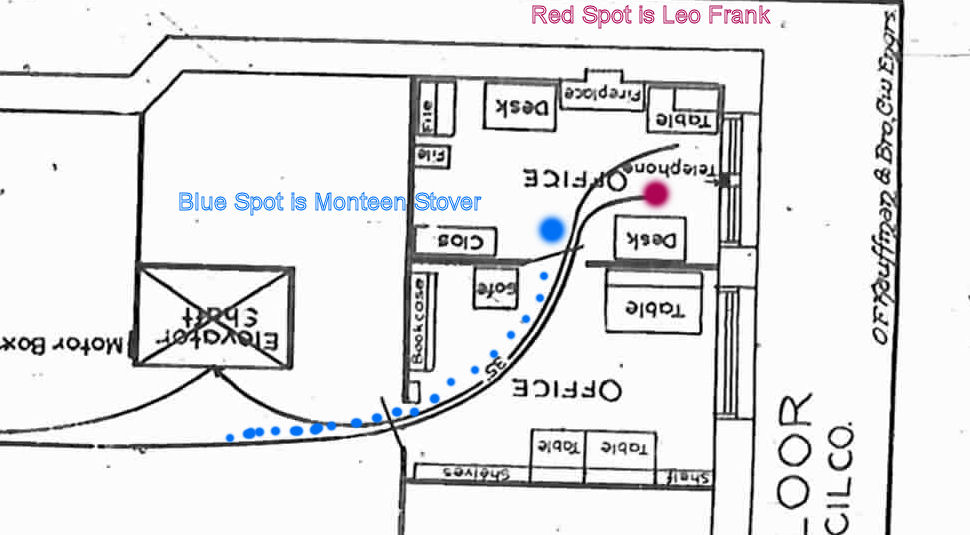

4. When Lee returned at six, Frank was even more nervous and agitated than two hours earlier, according to Lee. He was so nervous, he could not operate the time clock properly, something he had done hundreds of times before. (Leo Frank officially started to work at the National Pencil Company on Monday morning, August 10, 1908. Twenty-two days later, on September 1, 1908, he was elevated to the position of superintendent of the company, and served in this capacity until he was arrested on Tuesday morning, April 29, 1913.)

5. When Leo Frank came out of the building around six, he met not only Lee but John Milton Gantt, a former employee who was a friend of Mary Phagan. Lee says that when Frank saw Gantt, he visibly “jumped back” and appeared very nervous when Gantt asked to go into the building to retrieve some shoes that he had left there. According to E.F. Holloway, J.M. Gantt had known Mary for a long time and was one of the only employees Mary Phagan spoke with at the factory. Gantt was the former paymaster of the firm. Frank had fired him three weeks earlier, allegedly because the payroll was short about $1. Was Gantt’s firing a case of the dragon getting rid of the prince to get the princess? Was Frank jealous of Gantt’s closeness with Mary Phagan? Unlike Frank, Gantt was tall with bright blue eyes and handsome features.

6. After Frank returned home in the evening after the murder, he called Newt Lee on the telephone and asked him if everything was “all right” at the factory, something he had never done before. A few hours later Lee would discover the mutilated body of Mary Phagan in the pencil factory basement.

7. When police finally reached Frank after the body of Mary Phagan had been found, Frank emphatically denied knowing the murdered girl by name, even though he had seen her probably hundreds of times — he had to pass by her work station, where she had worked for a year, every time he inspected the workers’ area on the second floor and every time he went to the bathroom — and he had filled out her pay slip personally on approximately 52 occasions, marking it with her initials “M. P.” Witnesses also testified that Frank had spoken to Mary Phagan on multiple occasions, even getting a little too close for comfort at times, putting his hand on her shoulder and calling her “Mary.”

8. When police accompanied Frank to the factory on the morning after the murder, Frank was so nervous and shaking so badly he could not even perform simple tasks like unlocking a door.

9. Early in the investigation, Leo Frank told police that he knew that J.M. Gantt had been “intimate” with Mary Phagan, immediately making Gantt a suspect. Gantt was arrested and interrogated. But how could Frank have known such a thing about a girl he didn’t even know by name?

10. Also early in the investigation, while both Leo Frank and Newt Lee were being held and some suspicion was still directed at Lee, a bloody shirt was “discovered” in a barrel at Lee’s home. Investigators became suspicious when it was proved that the blood marks on the shirt had been made by wiping it, unworn, in the liquid. The shirt had no trace of body odor and the blood had fully soaked even the armpit area, even though only a small quantity of blood was found at the crime scene. This was the first sign that money was being used to procure illegal acts and interfere in the case in such a way as to direct suspicion away from Leo M. Frank. This became a virtual certainty when Lee was definitely cleared.

11. Leo Frank claimed that he was in his office continuously from noon to 12:35 on the day of the murder, but a witness friendly to Frank, 14-year-old Monteen Stover, said Frank’s office was totally empty from 12:05 to 12:10 while she waited for him there before giving up and leaving. This was approximately the same time as Mary Phagan’s visit to Frank’s office and the time she was murdered. On Sunday, April 27, 1913, Leo Frank told police that Mary Phagan came into his office at 12:03 PM. The next day, Frank made a deposition to the police, with his lawyers present, in which he said he was alone with Mary Phagan in his office between 12:05 and 12:10. Frank would later change his story again, stating on the stand that Mary Phagan came into his office a full five minutes later than that.

12. Leo Frank contradicted his own testimony when he finally admitted on the stand that he had possibly “unconsciously” gone to the Metal Room bathroom between 12:05 and 12:10 PM on the day of the murder.

13. The Metal Room, which Frank finally admitted at trial he might have “unconsciously” visited at the approximate time of the killing (and where no one else except Mary Phagan could be placed by investigators), was the room in which the prosecution said the murder occurred. It was also where investigators had found spots of blood, and some blondish hair twisted on a lathe handle — where there had definitely been no hair the day before. (When R.P. Barret left work on Friday evening at 6:00 PM, he had left a piece of work in his machine that he intended to finish on Monday morning at 6:30 AM. It was then he found the hair — with dried blood on it — on his lathe. How did it get there over the weekend, if the factory was closed for the holiday? Several co-workers testified the hair resembled Mary Phagan’s. Nearby, on the floor adjacent to the Metal Room’s bathroom door, was a five-inch-wide fan-shaped blood stain.)

14. In his initial statement to authorities, Leo Frank stated that after Mary Phagan picked up her pay in his office, “She went out through the outer office and I heard her talking with another girl.” This “other girl” never existed. Every person known to be in the building was extensively investigated and interviewed, and no girl spoke to Mary Phagan nor met her at that time. Monteen Stover was the only other girl there, and she saw only an empty office. Stover was friendly with Leo Frank, and in fact was a positive character witness for him. She had no reason to lie. But Leo Frank evidently did. (Atlanta Georgian, April 28, 1913)

15. In an interview shortly after the discovery of the murder, Leo Frank stated “I have been in the habit of calling up the night watchman to keep a check on him, and at 7 o’clock called Newt.” But Newt Lee, who had no motive to hurt his boss (in fact quite the opposite) firmly maintained that in his three weeks of working as the factory’s night watchman, Frank had never before made such a call. (Atlanta Georgian, April 28, 1913)

16. A few days later, Frank told the press, referring to the National Pencil Company factory where the murder took place, “I deeply regret the carelessness shown by the police department in not making a complete investigation as to finger prints and other evidence before a great throng of people were allowed to enter the place.” But it was Frank himself, as factory superintendent, who had total control over access to the factory and crime scene — who was fully aware that evidence might thereby be destroyed — and who allowed it to happen. (Atlanta Georgian, April 29, 1913)

17. Although Leo Frank made a public show of support for Newt Lee, stating Lee was not guilty of the murder, behind the scenes he was saying quite different things. In its issue of April 29, 1913, the Atlanta Georgian published an article titled “Suspicion Lifts from Frank,” in which it was stated that the police were increasingly of the opinion that Newt Lee was the murderer, and that “additional clews furnished by the head of the pencil factory [Frank] were responsible for closing the net around the negro watchman.” The discovery that the bloody shirt found at Lee’s home was planted, along with other factors such as Lee’s unshakable testimony, would soon change their views, however.

18. One of the “clews” provided by Frank was his claim that Newt Lee had not punched the company’s time clock properly, evidently missing several of his rounds and giving him time to kill Mary Phagan and return home to hide the bloody shirt. But that directly contradicted Frank’s initial statement the morning after the murder that Lee’s time slip was complete and proper in every way. Why the change? The attempt to frame Lee would eventually crumble, especially after it was discovered that Mary Phagan died shortly after noon, four hours before Newt Lee’s first arrival at the factory.

19. Almost immediately after the murder, pro-Frank partisans with the National Pencil Company hired the Pinkerton detective agency to investigate the crime. But even the Pinkertons, being paid by Frank’s supporters, eventually were forced to come to the conclusion that Frank was the guilty man. (The Pinkertons were hired by Sigmund Montag of the National Company at the behest of Leo Frank, with the understanding that they were to “ferret out the murderer, no matter who he was.” After Leo Frank was convicted, Harry Scott and the Pinkertons were stiffed out of an investigation bill totaling some $1300 for their investigative work that had indeed helped to “ferret out the murderer, no matter who he was.” The Pinkertons had to sue to win their wages and expenses in court, but were never able to fully collect. Mary Phagan’s mother also took the National Pencil Company to court for wrongful death, and the case settled out of court. She also was never able to fully collect the settlement. These are some of the unwritten injustices of the Leo Frank case, in which hard-working and incorruptible detectives were stiffed out of their money for being incorruptible, and a mother was cheated of her daughter’s life and then cheated out of her rightful settlement as well.) (Atlanta Georgian, May 26, 1913, “Pinkerton Man says Frank Is Guilty – Pencil Factory Owners Told Him Not to Shield Superintendent, Scott Declares”)

20. That is not to say that were not factions within the Pinkertons, though. One faction was not averse to planting false evidence. A Pinkerton agent named W.D. McWorth — three weeks after the entire factory had been meticulously examined by police and Pinkerton men — miraculously “discovered” a bloody club, a piece of cord like that used to strangle Mary Phagan, and an alleged piece of Mary Phagan’s pay envelope on the first floor of the factory, near where the factory’s Black sweeper, Jim Conley, had been sitting on the fatal day. This was the beginning of the attempt to place guilt for the killing on Conley, an effort which still continues 100 years later. The “discovery” was so obviously and patently false that it was greeted with disbelief by almost everyone, and McWorth was pulled off the investigation and eventually discharged by the Pinkerton agency.

21. It also came out that McWorth had made his “finds” while chief Pinkerton investigator Harry Scott was out of town. Most interestingly, and contrary to Scott’s direct orders, McWorth’s “discoveries” were reported immediately to Frank’s defense team, but not at all to the police. A year later, McWorth surfaced once more, now as a Burns agency operative, a firm which was by then openly working in the interests of Frank. One must ask: Who would pay for such obstruction of justice? — and why? (Frey, The Silent and the Damned, page 46; Indianapolis Star, May 28, 1914; The Frank Case, Atlanta Publishing Co., p. 65)

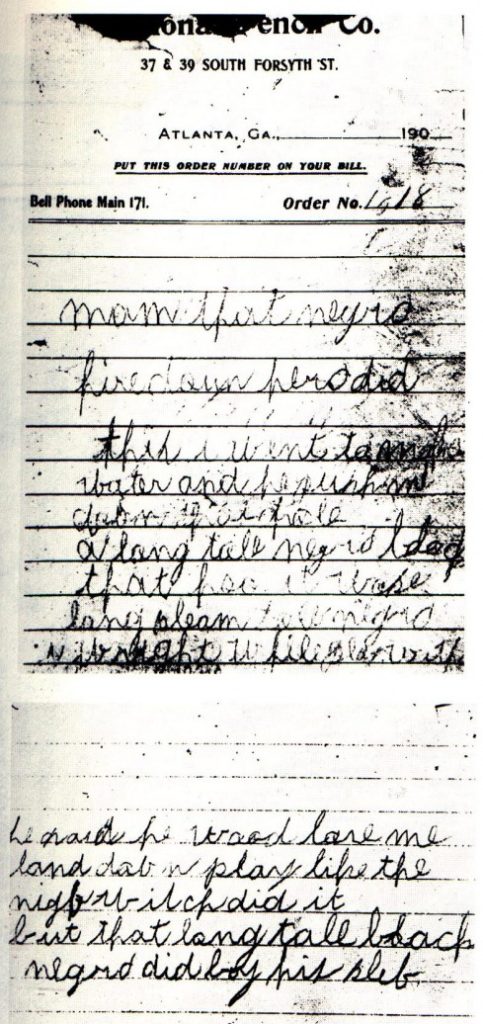

22. Jim Conley told police two obviously false narratives before finally breaking down and admitting that he was an accessory to Leo Frank in moving of the body of Mary Phagan and in authoring, at Frank’s direction, the “death notes” found near the body in the basement. These notes, ostensibly from Mary Phagan but written in semi-literate Southern black dialect, seemed to point to the night watchman as the killer. To a rapt audience of investigators and factory officials, Conley re-enacted his and Frank’s conversations and movements on the day of the killing. Investigators, and even some observers who were very skeptical at first, felt that Conley’s detailed narrative had the ring of truth.

23. At trial, the leading — and most expensive — criminal defense lawyers in the state of Georgia could not trip up Jim Conley or shake him from his story.

24. Conley stated that Leo Frank sometimes employed him to watch the entrance to the factory while Frank “chatted” with teenage girl employees upstairs. Conley said that Frank admitted that he had accidentally killed Mary Phagan when she resisted his advances, and sought his help in the hiding of the body and in writing the black-dialect “death notes” that attempted to throw suspicion on the night watchman. Conley said he was supposed to come back later to burn Mary Phagan’s body in return for $200, but fell asleep and did not return.

25. Blood spots were found exactly where Conley said that Mary Phagan’s lifeless body was found by him in the second floor metal room.

26. Hair that looked like Mary Phagan’s was found on a Metal Room lathe immediately next to where Conley said he found her body, where she had apparently fallen after her altercation with Leo Frank.

27. Blood spots were found exactly where Conley says he dropped Mary Phagan’s body while trying to move it. Conley could not have known this. If he was making up his story, this is a coincidence too fantastic to be accepted.

28. A piece of Mary Phagan’s lacy underwear was looped around her neck, apparently in a clumsy attempt to hide the deeply indented marks of the rope which was used to strangle her. No murderer could possibly believe that detectives would be fooled for an instant by such a deception. But a murderer who needed another man’s help for a few minutes in disposing of a body might indeed believe it would serve to briefly conceal the real nature of the crime from his assistant, perhaps being mistaken for a lace collar.

29. If Conley was the killer — and it had to be Conley or Frank — he moved the body of Mary Phagan by himself. The lacy loop around Mary Phagan’s neck would serve absolutely no purpose in such a scenario.

30. The dragging marks on the basement floor, leading to where Mary Phagan’s body was dumped near the furnace, began at the elevator — exactly matching Jim Conley’s version of events.

31. Much has been made of Conley’s admission that he defecated in the elevator shaft on Saturday morning, and the idea that, because the detectives crushed the feces for the first time when they rode down in the elevator the next day, Conley’s story that he and Frank used the elevator to bring Mary Phagan’s body to the basement on Saturday afternoon could not be true — thus bringing Conley’s entire story into question. But how could anyone determine with certainty that the “crushing” was the “first crushing”? And nowhere in the voluminous records of the case — including Governor Slaton’s commutation order in which he details his supposed tests of the elevator — can we find evidence that anyone made even the most elementary inquiry into whether or not the bottom surface of the elevator car was uniformly flat.

32. Furthermore, the so-called “shit in the shaft” theory of Frank’s innocence also breaks down when we consider the fact that detectives inspected the floor of the elevator shaft before riding down in the elevator, and found in it Mary Phagan’s parasol and a large quantity of trash and debris. Detective R.M. Lassiter stated at the inquest into Mary Phagan’s death, in answer to the question “Is the bottom of the elevator shaft of concrete or wood, or what?” that “I don’t know. It was full of trash and I couldn’t see.” There was so much trash there, the investigator couldn’t even tell what the floor of the shaft was made of! There may well have been enough trash, and arranged in such a way, to have prevented the crushing of the waste material when Frank and Conley used the elevator to transport Mary Phagan’s body to the basement. In digging through this trash, detectives could easily have moved it enough to permit the crushing of the feces the next time the elevator was run down.

33. The defense’s theory of Conley’s guilt involves Conley alone bringing Mary Phagan’s body to the basement down the scuttle hole ladder, not the elevator. But Lassiter was insistent that the dragging marks did not begin at the ladder, stating at the inquest: “No, sir; the dragging signs went past the foot of the ladder. I saw them between the elevator and the ladder.” Why would Conley pointlessly drag the body backwards toward the elevator, when his goal was the furnace? Why were there no signs of his turning around if he had done so? If Mary Phagan’s body could leave dragging marks on the irregular and dirty surface of the basement, why were there no marks of a heavy body being dumped down the scuttle hole as the defense alleged Conley to have done? Why did Mary Phagan’s body not have the multiple bruises it would have to have incurred from being hurled 14 feet down the scuttle hole to the basement floor below?

34. Leo Frank changed the time at which he said Mary Phagan came to collect her pay. He initially said that it was 12:03, then said that it might have been “12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07.” But at the inquest he moved his estimates a full five minutes later: “Q: What time did she come in? A: I don’t know exactly; it was 12:10 or 12:15. Q: How do you fix the time that she came in as 12:10 or 12:15? A: Because the other people left at 12 and I judged it to be ten or fifteen minutes later when she came in.” He seems to have no solid basis for his new estimate, so why change it by five minutes, or at all?

35. Pinkerton detective Harry Scott, who was employed by Leo Frank to investigate the murder, testified that he was asked by Frank’s defense team to withhold from the police any evidence his agency might find until after giving it to Frank’s lawyers. Scott refused.

36. Newt Lee, who was proved absolutely innocent, and who never tried to implicate anyone including Leo Frank, says Frank reacted with horror when Lee suggested that Mary Phagan might have been killed during the day, and not at night as was commonly believed early in the investigation. The daytime was exactly when Frank was at the factory, and Lee wasn’t. Here Detective Harry Scott testifies as to part of the conversation that ensued when Leo Frank and Newt Lee were purposely brought together: “Q: What did Lee say? A: Lee says that Frank didn’t want to talk about the murder. Lee says he told Frank he knew the murder was committed in daytime, and Frank hung his head and said ‘Let’s don’t talk about that!’” (Atlanta Georgian, May 8, 1913, “Lee Repeats His Private Conversation With Frank”)

37. When Newt Lee was questioned at the inquest about this arranged conversation, he confirms that Frank didn’t want to continue the conversation when Lee stated that the killing couldn’t possibly have happened during his evening and nighttime watch: “Q: Tell the jury of your conversation with Frank in private. A: I was in the room and he came in. I said, Mr. Frank, it is mighty hard to be sitting here handcuffed. He said he thought I was innocent, and I said I didn’t know anything except finding the body. ‘Yes,’ Mr. Frank said, ‘and you keep that up we will both go to hell!’ I told him that if she had been killed in the basement I would have known it, and he said, ‘Don’t let’s talk about that — let that go!’” (Atlanta Georgian, May 8, 1913, “Lee Repeats His Private Conversation With Frank”)

38. Former County Policeman Boots Rogers, who drove the officers to Frank’s home and then took them all, including Frank, back to the factory on the morning of April 27, said Frank was so nervous that he was hoarse — even before being told of the murder. (Atlanta Georgian, May 8, 1913, “Rogers Tells What Police Found at the Factory”)

39. Rogers also states that he personally inspected Newt Lee’s time slip — the one that Leo Frank at first said had no misses, but later claimed the reverse. The Atlanta Georgian on May 8 reported what Rogers saw: “Rogers said he looked at the slip and the first punch was at 6:30 and last at 2:30. There were no misses, he said.” Frank, unfortunately, was allowed to take the slip and put it in his desk. Later a slip with several punches missing would turn up. How can this be reconciled with the behavior of an innocent man?

40. The curious series of events surrounding Lee’s time slip is totally inconsistent with theory of a police “frame-up” of Leo Frank. At the time these events occurred, suspicion was strongly directed at Lee, and not at Frank.

41. When Leo Frank accompanied the officers to the police station later on during the day after the murder, Rogers stated that Leo Frank was literally so nervous that his hands were visibly shaking.

42. Factory Foreman Lemmie Quinn would eventually testify for the defense that Leo Frank was calmly sitting in his office at 12:20, a few minutes after the murder probably occurred. As to whether this visit really happened, there is some question. Quinn says he came to visit Schiff, Frank’s personal assistant, who wasn’t there — was he even expected to be there on a Saturday and holiday? — and stayed only two minutes or so talking to Frank in the office. Frank at first said there was no such visit, and only remembered it days later when Quinn “refreshed his memory.”

43. As reported by the Atlanta Georgian, City detective John Black said even Quinn initially denied that there was such a visit! “Q: What did Mr. Quinn say to you about his trip to the factory Saturday? A: Mr. Quinn said he was not at the factory on the day of the murder. Q: How many times did he say it? A: Two or three times. I heard him tell Detective Starnes that he had not been there.” (Atlanta Georgian, May 8, 1913, “Black Testifies Quinn Denied Visiting Factory”)

44. Several young women and girls testified at the inquest that Frank had made improper advances toward them, in one instance touching a girl’s breast and in another appearing to offer money for compliance with his desires. The Atlanta Georgian reported: “Girls and women were called to the stand to testify that they had been employed at the factory or had had occasion to go there, and that Frank had attempted familiarities with them. Nellie Pettis, of 9 Oliver Street, declared that Frank had made improper advances to her. She was asked if she had ever been employed at the pencil factory. No, she answered. Q: Do you know Leo Frank? A: I have seen him once or twice. Q: When and where did you see him? A: In his office at the factory whenever I went to draw my sister-in-law’s pay. Q: What did he say to you that might have been improper on any of these visits? A: He didn’t exactly say — he made gestures. I went to get sister’s pay about four weeks ago and when I went into the office of Mr. Frank I asked for her. He told me I couldn’t see her unless ‘I saw him first.’ I told him I didn’t want to ‘see him.’ He pulled a box from his desk. It had a lot of money in it. He looked at it significantly and then looked at me. When he looked at me, he winked. As he winked he said: ‘How about it?’ I instantly told him I was a nice girl. Here the witness stopped her statement. Coroner Donehoo asked her sharply: ‘Didn’t you say anything else?’ ‘Yes, I did! I told him to go to h–l! and walked out of his office.’” (Atlanta Georgian, May 9, 1913, “Phagan Case to be Rushed to Grand Jury by Dorsey”)

45. In the same article, another young girl testified to Frank’s pattern of improper familiarities: “Nellie Wood, a young girl, testified as follows: Q: Do you know Leo Frank? A: I worked for him two days. Q: Did you observe any misconduct on his part? A: Well, his actions didn’t suit me. He’d come around and put his hands on me when such conduct was entirely uncalled for. Q: Is that all he did? A: No. He asked me one day to come into his office, saying that he wanted to talk to me. He tried to close the door but I wouldn’t let him. He got too familiar by getting so close to me. He also put his hands on me. Q: Where did he put his hands? He barely touched my breast. He was subtle in his approaches, and tried to pretend that he was joking. But I was too wary for such as that. Q: Did he try further familiarities? A: Yes.”

46. In May, around the time of disgraced Pinkerton detective McWorth’s attempt to plant fake evidence — which caused McWorth’s dismissal from the Pinkerton agency — attorney Thomas Felder made his loud but mysterious appearance. “Colonel” Felder, as he was known, was soliciting donations to bring yet another private detective agency into the case — Pinkerton’s great rival, the William Burns agency. Felder claimed to be representing neighbors, friends, and family members of Mary Phagan. But Mary Phagan’s stepfather, J.W. Coleman, was so angered by this misrepresentation that he made an affidavit denying there was any connection between him and Felder. It was widely believed that Felder and Burns were secretly retained by Frank supporters. The most logical interpretation of these events is that, having largely failed in getting the Pinkerton agency to perform corrupt acts on behalf of Frank, Frank’s supporters decided to covertly bring another, and hopefully more “cooperative,” agency into the case. Felder and his “unselfish” efforts were their cover. Felder’s representations were seen as deception by many, which led more and more people to question Frank’s innocence. (Atlanta Georgian, May 15, 1913, “Burns Investigator Will Probe Slaying”)

47. Felder’s efforts collapsed when A.S. Colyar, a secret agent of the police, used a dictograph to secretly record Felder offering to pay $1,000 for the original Coleman affidavit and for copies of the confidential police files on the Mary Phagan case. C.W. Tobie, the Burns detective brought into the case by Felder, was reportedly present. Colyar stated that after this meeting “I left the Piedmont Hotel at 10:55 a.m. and Tobie went from thence to Felder’s office, as he informed me, to meet a committee of citizens, among whom were Mr. Hirsch, Mr. Myers, Mr. Greenstein and several other prominent Jews in this city.” (Atlanta Georgian, May 21, 1913, “T.B. Felder Repudiates Report of Activity for Frank”)

48. Felder then lashed out wildly, vehemently denied working for Frank’s friends, and declared that he thought Frank guilty. He even made the bizarre claim, impossible for anyone to believe, that the police were shielding Frank. It was observed of Felder that “when one’s reputation is near zero, one might want to attach oneself to the side one wants to harm in an effort to drag them down as you fall.” (Atlanta Georgian, May 21, 1913, “T.B. Felder Repudiates Report of Activity for Frank”)

49. Interestingly, C.W. Tobie, the Burns man, also made a statement shortly afterward — when his firm initially withdrew from the case — that he had come to believe in Frank’s guilt also: “It is being insinuated by certain forces that we are striving to shield Frank. That is absurd. From what I developed in my investigation I am convinced that Frank is the guilty man.” (Atlanta Constitution, May 27, 1913, “Burns Agency Quits the Phagan case”)

50. As his efforts crashed to Earth, Felder made this statement to an Atlanta Constitution reporter: “Is it not passing strange that the city detective department, whose wages are paid by the taxpayers of this city, should ‘hob-nob’ daily with the Pinkerton Detective Agency, an agency confessedly employed in this investigation to work in behalf of Leo Frank; that they would take this agency into their daily and hourly conference and repose in it their confidence, and co-operate with it in every way possible, and withhold their co-operation from W.J. Burns and his able assistants, who are engaged by the public and for the public in ferreting out this crime.” But what Felder failed to mention was that the Pinkertons’ main agent in Atlanta, Harry Scott, had proved that he could not be corrupted by the National Pencil Company’s money, so it is reasonable to conclude that the well-heeled pro-Frank forces would search elsewhere for help. The famous William Burns agency was really the only logical choice. To think that Felder and “Mary Phagan’s neighbors” were selflessly employing Burns is naive in the extreme: It means that Frank’s wealthy friends would just sit on their money and stick with the not at all helpful Pinkertons, who had just fired the only agent who tried to “help” Frank. (Atlanta Constitution, May 25, 1913, “Thomas Felder Brands the Charges of Bribery Diabolical Conspiracy”)

51. Colyar, the man who exposed Felder, also stated that Frank’s friends were spreading money around to get witnesses to leave town or make false affidavits. The Atlanta Georgian commented on Felder’s antics as he exited the stage: “It is regarded as certain that Felder is eliminated entirely from the Phagan case. It had been believed that he really was in the employ of the Frank defense up to the time that he began to bombard the public with statements against Frank and went on record in saying he believed in the guilt of Frank.” (Atlanta Georgian, May 26, 1913, “Lay Bribery Effort to Frank’s Friends”)

52. When Jim Conley finally admitted he wrote the death notes found near Mary Phagan’s body, Leo Frank’s reaction was powerful: “Leo M. Frank was confronted in his cell by the startling confession of the negro sweeper, James Connally [sic]. ‘What have you to say to this?’ demanded a Georgian reporter. Frank, as soon as he had gained the import of what the negro had told, jumped back in his cell and refused to say a word. His hands moved nervously and his face twitched as though he were on the verge of a breakdown, but he absolutely declined to deny the truth of the negro’s statement or make any sort of comment upon it. His only answer to the repeated questions that were shot at him was a negative shaking of the head, or the simple, ‘I have nothing to say.’” (Atlanta Georgian, May 26, 1913, “Negro Sweeper Says He Wrote Phagan Notes”)

53. When Jim Conley re-enacted, step by step, the sequence of events as he experienced them on the day of the murder, including the exact positions in which the body was found and detailing his assisting Leo Frank in moving Mary Phagan’s body and writing the death notes, Harry Scott of the Pinkerton Detective Agency stated: “‘There is not a doubt but that the negro is telling the truth and it would be foolish to doubt it. The negro couldn’t go through the actions like he did unless he had done this just like he said,’ said Harry Scott. ‘We believe that we have at last gotten to the bottom of the Phagan mystery.’ (Atlanta Georgian, May 29, 1913 Extra, “Conley Re-enacts in Plant Part He Says He Took in Slaying”)

54. In early June, Felder’s name popped up in the press again. This time he was claiming that his nemesis A.S. Colyar had in his possession an affidavit from Jim Conley confessing to the murder of Mary Phagan, and that Colyar was withholding it from the police. The police immediately “sweated” Conley to see if there was any truth in this, but Conley vigorously denied the entire story, and stated that he had never even met Colyar. Chief of Police Lanford said this confirmed his belief that Felder had been secretly working for Frank all along: “‘I attribute this report to Colonel Felder’s work,’ said the chief. ‘It merely shows again that Felder is in league with the defense of Frank; that the attorney is trying to muddy the waters of this investigation to shield Frank and throw the blame on another. This first became noticeable when Felder endeavored to secure the release of Conley. His ulterior motive, I am sure, was the protection of Frank. He had been informed that the negro had this damaging evidence against Frank, and Felder did all in his power to secure the negro’s release. He declared that it was a shame that the police should hold Conley, an innocent negro. He protested strenuously against it. Yet not one time did Felder attempt to secure the release of Newt Lee or Gordon Bailey on the same grounds, even though both of these negroes had been held longer than Conley. This to me is significant of Felder’s ulterior motive in getting Conley away from the police.’” Are such underhanded shenanigans on the part of Frank’s team the actions of a truly innocent man? (Atlanta Georgian, June 6, 1913, “Conley, Grilled by Police Again, Denies Confessing Killing”)

55. Much is made by Frank partisans of Georgia Governor Slaton’s 1915 decision to commute Frank’s sentence from death by hanging to life imprisonment. But when Slaton issued his commutation order, he specifically stated that he was sustaining Frank’s conviction and the guilty verdict of the judge and jury: “In my judgement, by granting a commutation in this case, I am sustaining the jury, the judge, and the appellate tribunals, and at the same time am discharging that duty which is placed on me by the Constitution of the State.” He also added, of Jim Conley’s testimony that Frank had admitted to killing Mary Phagan and enlisted Conley’s help in moving the body: “It is hard to conceive that any man’s power of fabrication of minute details could reach that which Conley showed, unless it be the truth.”

56. On May 8, 1913. the Coroner’s Inquest jury, a panel of six sworn men, voted with the Coroner seven to zero to bind Leo Frank over to the grand jury on the charge of murder after hearing the testimony of 160 witnesses.

57. On May 24, 1913, after hearing evidence from prosecutor Hugh Dorsey and his witnesses, the grand jury charged Leo M. Frank with the murder of Mary Phagan. Four Jews were on the grand jury of 21 persons. Although only twelve votes were needed, the vote was unanimous against Frank. An historian specializing in the history of anti-Semitism, Albert Lindemann, denies that prejudice against Jews was a factor and states that the jurors “were persuaded by the concrete evidence that Dorsey presented.” And this indictment was handed down even without hearing any of Jim Conley’s testimony, which had not yet come out. (Lindemann, The Jew Accused: Three Anti-Semitic Affairs, Cambridge, 1993, p. 251)

58. On August 25, 1913, after more than 29 days of the longest and most costly trial in Southern history up to that time, and after two of South’s most talented and expensive attorneys and a veritable army of detectives and agents in their employ gave their all in defense of Leo M. Frank, and after four hours of jury deliberation, Frank was unanimously convicted of the murder of Mary Phagan by a vote of twelve to zero.

59. The trial judge, Leonard Strickland Roan, had the power to set aside the guilty verdict of Leo Frank if he believed that the defendant had not received a fair trial. He did not do so, effectively making the vote 13 to zero.

60. Judge Roan also had the power to sentence Frank to the lesser sentence of life imprisonment, even though the jury had not recommended mercy. On August 26, 1913, Judge Roan affirmed the verdict of guilt, and sentenced Leo Frank to death by hanging.

61. On October 31, 1913, the court rejected a request for a new trial by the Leo Frank defense team, and re-sentenced Frank to die. The sentence handed down by Judge Benjamin H Hill was set to be carried out on Frank’s 30th birthday, April 17, 1914.

62. Supported by a huge fundraising campaign launched by the American Jewish community, and supported by a public relations campaign carried out by innumerable newspapers and publishing companies nationwide, Leo Frank continued to mount a prodigious defense even after his conviction, employing some of the most prominent lawyers in the United States. From August 27, 1913, to April 22, 1915 they filed a long series of appeals to every possible level of the United States court system, beginning with an application to the Georgia Superior Court. That court rejected Frank’s appeal as groundless.

63. The next appeal by Frank’s “dream team” of world-renowned attorneys was to the Georgia Supreme Court. It was rejected.

64. A second appeal was then made by Frank’s lawyers to the Georgia Supreme Court, which was also rejected as groundless.

65. The next appeal by Frank’s phalanx of attorneys was to the United States Federal District Court, which also found Frank’s arguments unpersuasive and turned down the appeal, affirming that the guilty verdict of the jury should stand.

66. Next, the Frank legal team appealed to the highest court in the land, the United States Supreme Court, which rejected Frank’s arguments and turned down his appeal.

67. Finally, Frank’s army of counselors made a second appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court — which was also rejected, allowing Leo Frank’s original guilty verdict and sentence of death for the murder by strangulation of Mary Phagan to stand. Every single level of the United States legal system — after carefully and meticulously reviewing the trial testimony and evidence — voted in majority decisions to reject all of Leo Frank’s appeals, and to preserve the unanimous verdict of guilt given to Frank by Judge Leonard Strickland Roan and by the twelve-man jury at his trial, and to affirm the fairness of the legal process which began with Frank’s binding over and indictment by the seven-man coroner’s jury and 21-man grand jury.

68. It is preposterous to claim that these men, and all these institutions, North and South — the coroner’s jury, the grand jury, the trial jury, and the judges of the trial court, the Georgia Superior Court, the Georgia Supreme Court, the U.S. Federal District Court, and the United States Supreme Court — were motivated by anti-Semitism in reaching their conclusions.

69. Even in deciding to commute Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment, Governor John Slaton explicitly affirmed Frank’s guilty verdict. He explained that only the jury was the proper judge of the meaning of the evidence and the veracity of the witnesses placed before it. He said in the commutation order itself: “Many newspapers and non-residents have declared that Frank was convicted without any evidence to sustain the verdict. In large measure, those giving expression to this utterance have not read the evidence and are not acquainted with the facts. The same may be said regarding many of those who are demanding his execution. In my judgement, no one has a right to an opinion who is not acquainted with the evidence in the case, and it must be conceded that those who saw the witnesses and beheld their demeanor upon the stand are in the best position as a general rule to reach the truth.”

70. In May of 1915, the Georgia State Prison Board voted two to one against a clemency petition — which, even if successful, would not have changed the guilty verdict of Leo M. Frank.

71. In 1982 Alonzo Mann, who in 1913 at 13 years old had been the office boy for the National Pencil Company, made a sensation in the press by denying the sworn testimony he had made at the Leo Frank trial, and stating his belief that Jim Conley was the real killer of Mary Phagan. In 1913, Mann had testified that he left the office on the day of the murder at 11:30 AM. In 1982, he changed the time and told a quite different story, as follows:

Mann said that he left the factory at noon, half an hour later than in his testimony. It was Confederate Memorial Day and a parade and other festivities were scheduled. Mann was to meet his mother, he says, but could not find her and “returned to work” shortly after noon. When he entered the building, he says, he saw Jim Conley carrying the limp body of a girl on the first floor: “He wheeled on me and in a voice that was low but threatening he said ‘If you ever mention this I’ll kill you.’”

Mann claims he then left the building and ran home, telling his mother what he’d seen. Mann says that his parents advised him to keep silent to avoid publicity. And he did keep silent for many, many years. (Jim Conley is reported to have died in 1957 — another report says 1962 — and presumably his death threat did not survive his demise.)

There are several problems with Mann’s story. First, if true, it proves only that at some point Conley was carrying Phagan’s body by himself, without Frank’s help. Conley already admits this — though he says that he found the body too heavy for himself alone while still on the second floor, and that the elevator brought them directly to the basement. So Mann’s story really doesn’t address anything except two minor details of Conley’s testimony, neither of which are determinative of guilt. (Mann was poor, suffering with a heart condition, and facing considerable medical expenses when he “went public” with his claims.)

72. Why would a 13-year-old Alonzo Mann “return to work” on a holiday if he didn’t have to? And why “return to work” if he apparently wasn’t even scheduled to do so? Were office boys permitted to make their own hours in 1913? When other workers — such as Mary Phagan, for example — hadn’t sufficient supplies in their department, they were immediately laid off until the supplies came in. Surely such economy would dictate that office boys would only come in when authorized and asked to do so.

73. If Alonzo Mann had such a definite appointment to meet his mother in town — so definite as to cause him to return to work after just a few minutes when he failed to immediately find her — why, then, was she waiting at home just a few minutes after that?

74. Why would white parents, like Alonzo Mann’s, in the racially conscious and segregated Atlanta, Georgia of 1913, tell their white son not to tell the police about a guilty black murderer, when the result of not telling the police would ultimately result in an innocent, clean cut, white man, Leo Frank — the man who gave their son a highly prized job — going to gallows as an innocent man?

75. And why would Alonzo Mann’s parents then allow their 13-year-old son to report to work at the huge and cavernous National Pencil Company factory on Monday morning, April 28, 1913 — two days after he was threatened with death by a murderer carrying a dead or dying white girl on his shoulder — knowing that the murderer would still be there, and knowing that there were many dark and secluded places in said factory where their son might come to harm? Jim Conley reported back to work that Monday, as did Alonzo Mann and the approximately 170 other employees, who were naturally expected to be back at work after the holiday weekend. Jim Conley was not arrested until the first day of May.

76. If Alonzo Mann really walked in on Jim Conley carrying Mary Phagan’s body a few minutes after noon, and then turned around and left the building, why didn’t he see Monteen Stover?

77. If Jim Conley really attacked Mary Phagan at the foot of the stairs as Alonzo Mann suggests, why didn’t Leo Frank hear her scream or any sounds of a struggle? He was only 40 feet away.

78. Several witnesses — for both the prosecution and the defense — testified that they saw Jim Conley sitting, doing nothing, in the dark recesses of the lobby of the National Pencil Company on the morning of the murder. Does this fit the contention of the prosecution that Frank requested Conley’s presence on that day, as he had on others, so Conley could be a lookout while Frank was “chatting” with a teenage girl? Or does it make more sense to believe that Conley really believed he could get away with loafing on company property without permission all morning? Did black janitors in 1913 also have the right to make their own working hours, even on a holiday when there would have been little call for their services — and then, after showing up for “work,” not work at all?

79. Does it really make sense that the somewhat literate and fairly intelligent Jim Conley, a black man in the extremely race-conscious and white-dominated Atlanta of 1913, where lynch law often reigned supreme, actually thought he could get away with attacking and killing a white girl just a few feet away from the unlocked front door of the factory where he worked, in the highest-traffic area of the building? And does it make sense that he would do so for $1.20 — Mary Phagan’s entire pay — as the defense alleged? If Conley was plotting to rob someone, does it make sense that he would choose such a place to do so — or choose from a pool of potential victims considerably poorer than he was?

80. The fatal Saturday was a holiday. Jim Conley had been paid his $6.05 salary the evening before. By his standards, he had plenty of money — and it would have been very hard to drink it down very much on Friday, at a nickel a pint in those days. Conley was a man who liked his beer and billiards, and the town was wide open for that kind of fun all day. Why was he there at the factory, then? He certainly wouldn’t have wanted to be there, doing apparently nothing for hours on end. He also ran the risk of being disciplined if he was loafing there without permission. He was manifestly not sweeping, his ostensible job, on that day — he was just sitting, watching. The only reasonable explanation is that his boss, Leo Frank, had asked him to be there for that very purpose.

81. The relationship of Leo Frank and the National Pencil Company to Jim Conley was a strange one. Why was Jim Conley’s sweeper’s salary much higher — $6.05 versus $4.05 — than the average of the white employees, many of whom were skilled machine operators? Could it be that Conley served a very important but secret purpose for Leo Frank, exactly as the prosecution alleged? Could he have had knowledge that could potentially hurt Leo Frank, justifying Frank granting him special privileges?

82. According to a female National Pencil Company employee, Jim Conley was once caught “sprinkling” (urinating) on the pencils, surely a very serious offense. But Conley was never fired. (Trial Testimony of Herbert George Schiff, Brief of Evidence, Leo Frank Trial, August, 1913) Again, could it be that James Conley served a very important but secret purpose for Leo Frank, and could he have possessed knowledge that could damage Frank?

83. According to fellow employee Gordon Bailey (Leo Frank trial, Brief of Evidence, August, 1913) Jim Conley was not always required to punch the time clock. Why would the “Negro sweeper,” as they called him, surely the lowest-ranking employee in the pencil factory hierarchy, be given such an unprecedented privilege by Leo M. Frank? Why was Jim Conley the only person out of the 170 factory employees who didn’t have to punch the time clock — unless Jim Conley was more than meets the eye?

84. In 1983, the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL), along with other Jewish groups, spearheaded a campaign to get the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles to issue a posthumous pardon to Leo Frank, basing their case largely on the 1982 statement of Alonzo Mann. The Board found that Mann’s statement added no new evidence to the case. They also noted that Governor Slaton in his 1915 commutation decision had already considered that the elevator may not have been used to move Mary Phagan’s body, but nevertheless he upheld Frank’s conviction. The ADL’s petition was denied and Leo Frank’s guilty verdict was affirmed.

85. The ADL and other Jewish groups filed again in 1986 for Leo Frank to be pardoned by the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. This time the Jewish groups claimed that, because the state of Georgia had failed to prevent the lynching of Leo Frank after his sentence was commuted by Governor Slaton, Leo Frank’s rights had been violated and he should be pardoned on that basis alone. A great deal of pressure was applied to the Board via sensational stories, editorials, and even fictionalized accounts in the media. With this far more limited claim — that Frank was not protected from lynching as he ought to have been — the Board was compelled to agree. But the Board would not and did not exonerate Leo Frank of his guilt for the strangulation death of Mary Anne Phagan on April 26, 1913. His conviction for her murder still stands.

86. Lucille Selig Frank, Leo Frank’s wife, is known as a fiercely loyal spouse who passionately defended her husband against charges both criminal and moral, and stood by his side during his trial and appeals. There are some indications, however, that she may have early on during the Mary Phagan case believed that her husband had not been entirely faithful and had in fact killed Mary Phagan, probably believing it to be accidental. Long after her husband’s death, she may have returned to those views.

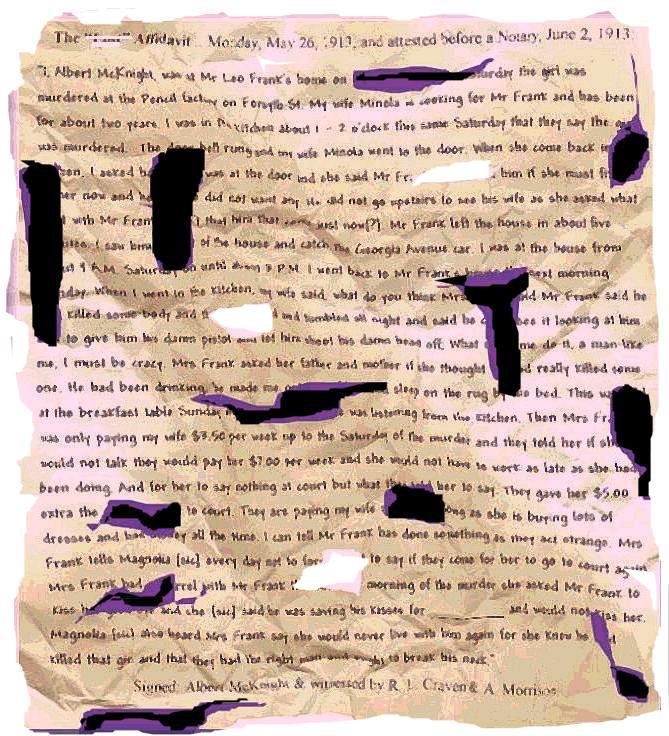

State’s Exhibit J at Leo Frank’s trial consisted of an affidavit by Minola McKnight, the Frank’s black cook. Mrs. McKnight first came to the attention of the authorities when her husband told police that his wife had heard some startling revelations while working at the Frank residence the evening of the murder — namely, that Leo Frank had drunkenly and remorsefully admitted to his wife that he and a girl “had been caught” at the factory, that he “didn’t know why he would murder” her, and that he asked his wife Lucille to get him a pistol so he could kill himself.

These are Minola McKnight’s own words from the affidavit: “Sunday, Miss Lucille said to Mrs. Selig that Mr. Frank didn’t rest so good Saturday night; she said he was drunk and wouldn’t let her sleep with him… Miss Lucille said Sunday that Mr. Frank told her Saturday night that he was in trouble, and that he didn’t know the reason why he would murder, and he told his wife to get his pistol and let him kill himself… When I left home to go to the solicitor general’s office, they told me to mind how I talked. They pay me $3.50 a week, but last week they paid me $4.00, and one week she paid me $6.50. Up to the time of the murder I was getting $3.50 a week and the week right after the murder I don’t remember how much she paid me, and the next week they paid me $3.50, and the next week they paid me $6.50, and the next week they paid me $4.00 and the next week they paid me $4.00. One week, I don’t remember which one, Mrs. Selig gave me $5, but it wasn’t for my work, and they didn’t tell me what it was for, she just said, ‘Here is $5, Minola.’ I understood that it was a tip for me to keep quiet. They would tell me to mind how I talked and Miss Lucille gave me a hat.”

(Leo Frank admitted that he bought a box of chocolates for his wife on the way home on the evening of the day of the murder.) Minola McKnight would tell a different story after she was back in the Frank household, however. She then repudiated her affidavit and said police had coerced it from her. But neither she nor anyone else has given a credible motive for Minola’s husband to have lied.

After Leo Frank’s arrest, Lucille did not visit her husband for some thirteen days, after which she began her loyal and indomitable defense of him. What made her wait? Leo Frank’s explanation was that Lucille had to be “physically restrained” because she wanted so badly to be locked up with him in jail. Judge for yourself the credibility of this explanation against that offered in State’s Exhibit J.

Lucille Frank died in 1957, and in her will she specifically directed that she be cremated and thus not buried next to, or with, her first and only husband, Leo Frank — even though a plot had already been provided for her next to him.

87. Leonard Dinnerstein is an author who has made almost his entire career writing about anti-Semitism, with a special concentration on proving that Leo Frank was a victim of anti-Semitism. His book, The Leo Frank Case, is promoted as a canonical work — and is one of the main sources for the claims that 2) anti-Semitism was pervasive in 1913 Georgia and 2) that anti-Semitism was the major factor in the prosecution and conviction of Frank.

Both of these claims are hoaxes, as shown by Elliot Dashfield writing in The American Mercury: “Dinnerstein makes his now-famous claim that mobs of anti-Semitic Southerners, outside the courtroom where Frank was on trial, were shouting into the open windows ‘Crack the Jew’s neck!’ and ‘Lynch him!’ and that members of the crowd were making open death threats against the jury, saying that the jurors would be lynched if they didn’t vote to hang ‘the damn sheeny.’

“But not one of the three major Atlanta newspapers, who had teams of journalists documenting feint-by-feint all the events in the courtroom, large and small, and who also had teams of reporters with the crowds outside, ever reported these alleged vociferous death threats. And certainly such a newsworthy event could not be ignored by highly competitive newsmen eager to sell papers and advance their careers. Do you actually believe that the reporters who gave us such meticulously detailed accounts of this Trial of the Century, even writing about the seating arrangements in the courtroom, the songs sung outside the building by folk singers, and the changeover of court stenographers in relays, would leave out all mention or notice of a murderous mob making death threats to the jury?

“During the two years of Leo Frank’s appeals, none of these alleged anti-Semitic death threats were ever reported by Frank’s own defense team. There is not a word of them in the 3,000 pages of official Leo Frank trial and appeal records – and all this despite the fact that Reuben Arnold [Frank’s attorney] made the claim during his closing arguments that Leo Frank was tried only because he was a Jew… Yet, thanks to Leonard Dinnerstein, this fictional episode has entered the consciousness of Americans of all stations as ‘history’ – as one of the pivotal facts of the Frank case.”

88. In his book attempting to exonerate Frank, Leonard Dinnerstein knowingly repeats the preposterous 1964 hoax perpetrated by “hack writer and self-promoter Pierre van Paassen” (Dashfield, The American Mercury, October 2012):

“Van Paassen claimed that there were in existence in 1922 X-ray photographs at the Fulton County Courthouse, taken in 1913, of Leo Frank’s teeth, and also X-ray photographs of bite marks on Mary Phagan’s neck and shoulder – and that anti-Semites had suppressed this evidence. Van Paassen further alleged – and Dinnerstein repeated – that the dimensions of Frank’s teeth did not match the ‘bite marks,’ thereby exonerating Frank… Since Dinnerstein is such a lofty academic scholar and professor, perhaps he simply forgot to ask a current freshman in medical school if it was even possible to X-ray bite marks on skin in 1913 – or necessary in 2012, for that matter – because it’s not. In 1913, X-ray technology was in its infancy and never used in any criminal case until many years after Leo Frank was hanged.” Furthermore, there is no hint anywhere in the massive official records of the Leo Frank trial and appeals of any “bite marks.” If Leo Frank is manifestly and truly innocent, why do his supporters have to engage in such outrages against truth?

89. Far from being a region rife with hatred for Jews, the South in general and Atlanta in particular were regarded by Jews as a haven and as a place nearly free from the anti-Semitism they suffered in other parts of the nation and the world. Even today, and even after Jewish-gentile relations there were strained by the Frank case and by Jewish support for the civil rights revolution, the Christians who form most of the population of the South are stoutly pro-Jewish. The South is the center of Christian Zionism and American support for the Jewish state of Israel.

90. Harry Golden wrote in the American Jewish Committee’s magazine Commentary that early “Bonds for Israel” salesmen would purposely seek out Southern Christians, since they were almost all passionately pro-Jewish and pro-Israel. When Southerners were asked about their reasons for supporting Zionism, Golden said that a typical Southerner’s response was “It’s in the book!” — meaning, of course, the Bible. This attitude had deep roots and certainly did not materialize in 1948.

91. The writer Scott Aaron gives insight into Southern attitudes toward Jews when he says: “In the race-conscious South of 1913, Jews were considered white. In fact, in the newspapers of Atlanta before, during, and after the trial of Leo Frank for the murder of Mary Phagan, Frank was referred to as a ‘white man’ on innumerable occasions by reporters, witnesses, African-Americans, fellow Jews, pro-Frank partisans, and anti-Frank polemicists. Jews, furthermore, were not known for violent acts or crimes, nor feared as violators of white women. If anything, they were seen as an unusually industrious, intelligent, and law-abiding segment of society, even if they were a bit peculiar in their religious views.

“Marriage between Jews and Christians might have raised a few eyebrows in both communities – just as did intermarriage between members of widely different Christian denominations – but it was far from unknown, and such couples were not ostracized. In fact, Leo Frank’s own brother-in-law, Mr. Ursenbach, with whom he canceled an appointment to see a baseball game on the day Mary Phagan was killed, was a Christian.

“If there was prejudice against Leo Frank in 1913 Atlanta, it was almost certainly not because he was a Jew. He was, however, a capitalist, a business owner, a manager, an employer of child labor, and a Northerner with an Ivy League education. He also came to be known during the course of the trial as sexually profligate. These facts probably did count against him.”

92. Aaron also cites a study funded and published by a Jewish group: “John Higham, in his ‘Social Discrmination Against Jews 1830 – 1930,’ a work commissioned by the American Jewish Committee, called the South ‘historically the section least inclined to ostracize Jews,’ and drew attention to the ‘striking Southern situation’ of almost no discrimination against Jews there. True, Jewish-Gentile relations had somewhat declined there by the mid-twentieth century, and the massive campaign during the Frank appeals to paint his prosecution, and the South generally, as anti-Semitic — and the eventual creation of the Anti-Defamation League in the wake of Frank’s death — played their part in this change…

“But the aftermath of the Frank trial had no part, of course, in the attitudes of the people of Atlanta on the day Mary Phagan was murdered. All things considered, the South in general and Atlanta in particular seem to have been, if anything, safe havens for Jews where they might escape from the anti-Semitism that was rampant around the beginning of the last century.”

93. Southern attitudes toward Jews can be further gauged by the fact that, during the Civil War, Southerners made a Jew their Secretary of the Treasury: Judah P. Benjamin was the first Jewish appointee to any Cabinet position in any North American government. Benjamin also served as Attorney General, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War for the Confederate States of America. He was so highly regarded that his portrait graced the paper money of the South. Meanwhile, around the same time, Northern general Ulysses S. Grant issued an order physically expelling all Jews from the parts of the South under his control, even demanding that they leave a huge multi-state area “within 24 hours.”

The claim that a pervasive and vicious anti-Semitism was the real reason for the prosecution and conviction of Leo Frank is an absurd lie and a fantastic misrepresentation of history. Nevertheless, it is now the stuff of innumerable works of alleged scholarship, drama, and fiction, and is viewed by naive students who are exposed to such works as the central “truth” of the case. If Leo Frank were innocent, why would his supporters have to fabricate such blatant impostures and engage in emotional blackmail on a colossal scale?

94. Researcher Allen Koenigsberg states that some of the most intriguing and important parts of Minola McKnight’s sworn affidavits have, for some reason or other, been completely omitted from the current literature on the Frank case:

“One of the most intriguing circumstances in the pre-trial development of this case involved a document signed by the black cook in the Frank/Selig household (Minola McKnight). Frank’s attorneys would long argue that it was coerced by the police as a result of ‘third degree methods.’ Since 1913, it has never been shown in its entirety, and we are glad to present it here [ http://www.leofrankcase.com/ ]. Also unmentioned in the last nine decades is the sequence of events that led up to its appearance. Minola would make three affidavits in all (May 3rd, June 2nd and 3rd), but her overnight incarceration was specifically caused by her husband Albert’s statement made on May 26, and notarized on June 2nd [ also at http://www.leofrankcase.com/ ]. This description of events has never been cited, with only an oblique reference in the Samuels’ Night Fell on Georgia (1956).

“The most striking sentence (and odd omission) is shown here for the first time: ‘Mrs. Frank had a quarrel with Mr. Frank the Saturday morning of the murder she asked Mr. Frank to kiss her good bye and she said he was saving his kisses for _______ and would not kiss her.‘ Readers may wish to consider its authenticity, as new light is shed on why Leo Frank ‘so thoughtfully’ bought his wife a box of chocolates from Jacobs’ Pharmacy just before returning home at 6:30 PM on April 26th.” (LeoFrankCase.Com, Retrieved 2012).

95. Much has been made of the fact that Jim Conley’s attorney, William M. Smith, eventually believing his own client to be guilty, made an analysis of the language used by Conley on the stand and, comparing it to the language used in the death notes, concluded that the real author of the notes was Conley. Therefore, Smith’s theory went, the notes had not been dictated by Leo Frank as Conley had testified. Many greeted this “revelation” with well-deserved derision. Few believed that Frank would have insisted that Conley copy his language exactly, word for word (though Hugh Dorsey made the mistake of suggesting this was so in his closing arguments). In fact, the death notes would serve their intended purpose — to place blame for the murder on a black man — much more effectively by being written in the natural language of an authentic speaker of Southern black dialect, and surely that is a fact that no intelligent murderer would fail to see and act upon.

96. In his book, A Little Girl Is Dead, writer Harry Golden, though not incapable of objective journalism (for example, he once reported that Southerners had unusually favorable attitudes to Jews), may have perpetrated the most outrageous hoax in the Frank case. Golden claimed that Jim Conley had made a deathbed confession to the murder of Mary Phagan. But famed pro-Frank researcher and author Steve Oney (very charitably) says of Golden that this was “wishful thinking.”

Oney went to great lengths to follow up on Golden’s claim: “Over the last few years legal aides have rifled through microfilm files in libraries across the South searching for news of Conley’s confession. They have found nothing.” (Oney, “The Lynching of Leo Frank,” Esquire, September 1985)

97. It seems unlikely that Hugh Dorsey was motivated by anti-Semitism in his prosecution of Leo Frank, considering that a partner in his law firm was Jewish. It’s preposterous to even have to ask the question, but if Dorsey hated Jews enough to send one to the gallows as an innocent man, why would he tolerate — and proudly claim, as he did at trial — such a close association with a Jewish man? And, if Dorsey was guilty of such vicious malice against Jews, why would his partner continue the association himself? (Closing arguments of Hugh Dorsey, Leo Frank trial)

98. Why did the Leo Frank defense team, consisting of some of the most skilled attorneys in the state, refuse to cross-examine 20 young women and girls who testified that Frank had a bad moral character? Under Georgia law, the prosecution was only allowed to use these witnesses’ testimony to enter the general fact that Frank’s character was bad. Under cross-examination, though, the defense could have forced the girls and women to give specific reasons and relate specific incidents that supported their opinion, and trip them up if they could. Why, then, did they not do so? The only reasonable answer: They knew Leo Frank’s character, and they did not dare allow any specifics to go before the jury.

99. One of the most bizarre hoaxes in the Phagan case was that surrounding insurance salesman W.H. Mincey. On the afternoon of the murder, Mincey claimed that Jim Conley, on the public streets of Atlanta and with no prompting — and for no apparent reason whatever — confessed to murdering a girl that very day.

According to the contemporary book The Frank Case, p. 66: “Mincey asserted that late in the afternoon he was at the corner of Electric avenue and Carter streets, near the home of Conley, when he approached the black, asking that he take an insurance policy. The negro told him, he said, to go along, that he was in trouble. Asked what his trouble was, Mincey swore that Conley replied he had killed a girl. ‘You are Jack the ripper, are you?’ said Mincey. ‘No,’ he says Conley replied, ‘I killed a white girl and you better go along or I will kill you.’”

That this tale could be accepted by any man in possession of his reason is doubtful, but nevertheless the Frank defense team seriously asserted in court their intention to call Mincey as a witness. They withdrew him, however, after the prosecution was said to have discovered Mincey’s problematic relationship with the truth and had 25 witnesses prepared to impeach him — and furthermore intended to produce copies of several books Mincey had written on the subject of “mind reading.”

100. Mary Phagan’s grand-niece, Mary Phagan Kean, relates in her book The Murder of Little Mary Phagan that her grandfather William Joshua Phagan, Jr. (Mary Phagan’s brother) confronted Jim Conley in private in 1934, and was ultimately convinced that the former factory sweeper was telling the truth. At times so emotionally moved that he could barely hold back tears, William Phagan finally told Conley that he believed him — and said that, if he had thought he was lying, “I’d kill you myself.” After the intense meeting was over, Jim Conley and Mary Phagan’s brother went out for a drink.

In truth, there are more — far more — than 100 reasons to believe that Leo Frank was guilty of murdering Mary Phagan. There are far more than 100 reasons to believe that the claim of widespread “Southern anti-Semitism,” virtually promoted as gospel today, is a complete and malicious fraud. There are far more than 100 reasons to believe that Frank’s defenders have used perjury, fraud, and outright hoaxes to impose their view of the case on an unsuspecting public.

I urge each and every one of you to read the original source materials I have catalogued in the Appendix which follows this article. Only by seeing what the jury saw — by reading what the people of Atlanta read as events unfolded — uncensored and without the nuance and spin of modern authors who are, with but a very few exceptions, uniformly dedicated to one side — can you truly understand the tragedy of little Mary Phagan and the whirlwind her death unleashed.

In my opinion, the most horrible imposture, the real injustice, in the Frank case as it stands today is that millions of trusting men and women, children and students, all across the world have been forcefully imprinted, by a relentless multimillion-dollar media campaign, with the idea that Leo Frank — the monster who almost certainly abused and strangled bright and beautiful Mary Anne Phagan to death — is the “real victim” in this case.

* * *

APPENDIX

_________

Full archive of Atlanta Georgian newspapers relating to the murder and subsequent trial

The Leo Frank case as reported in the Atlanta Constitution

The Leo Frank Case (Mary Phagan) Inside Story of Georgia’s Greatest Murder Mystery 1913

The Murder of Little Mary Phagan by Mary Phagan Kean

American State Trials, volume X (1918) by John Lawson